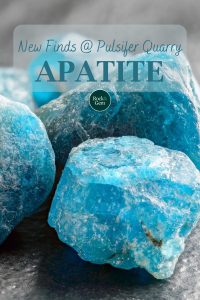

Apatite is a favorite collector’s mineral with a dizzying array of beautiful colors, such as blue apatite, and interesting crystal habits. Perhaps the most famous apatite locality in North America, and indeed the world, is the Pulsifer Quarry in Maine.

For almost a century, the Pulsifer Quarry was the source of some of the finest purple apatite specimens and gemstones ever found. However, no apatite was found there for decades following finds in 1996. Many assumed that the Pulsifer Quarry was extinct. But in the summer and fall of 2022, renewed activity at the quarry resulted in a new find of beautiful purple apatite specimens, with the promise of more to come.

About Apatite

Apatite is included on many blue gems and minerals lists. It is not one mineral species. It is a group of calcium phosphates with either fluorine, chlorine, or hydroxyl groups, respectively known as fluorapatite, chlorapatite, and hydroxylapatite. Fluorapatite is the most common species and includes the material from the Pulsifer Quarry. It is also the one most people are referring to when they say “apatite.”

Apatite occurs in a variety of geological environments but can be well developed in granitic pegmatites. It may be colorless, white, brown, green, yellow, blue or purple. In apatite, the purple color is caused by manganese. Purple apatite is found in a number of localities around the world, including several in Maine. “Royal purple” refers to a rich hue of purple. Royal purple apatite only occurs in a few localities and the Pulsifer Quarry is widely considered the best.

Courtesy Dan Namowitz

Pulsifer Quarry

Pulsifer Quarry was first worked by landowner, Pitt Pembroke Pulsifer in 1900. He found thousands of crystals, including one known as the “Roebling Apatite.” Weighing just over 100 grams, it is now housed at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. The quarry was worked off and on by several individuals through the twentieth century. In 1972, Irving “Dudy” Groves obtained ownership of the property and the mineral rights, which, on his passing in 2005, passed to his widow, Mary Groves, who still owns them.

The Pulsifer Quarry is located on aptlynamed Mt. Apatite, in Auburn, Maine. Actually a hill rather than a mountain, Mt. Apatite hosts several quarries that have produced interesting minerals. The “Eastern Quarries,” which include the Hatch, Greenlaw, and Maine Feldspar Quarries, are owned by the city of Auburn. The “Western Quarries,” including the Keith, Dionne, Wade, Raines, and Hole-in-the-Ground (Groves) Quarries, as well as the Pulsifer, are owned by Mary Groves. All of these sites are complex granitic pegmatites, for which Maine is famous.

Besides apatite, these localities are known for tourmaline (schorl and elbaite), garnet (almandine and spessartine), quartz, beryl and a host of rarer species, such as gahnite. Even though they are within a couple hundred meters of each other, the development of minerals in the Western Quarries varies. For example, purple apatite can be found at the Hole-in-the-Ground Quarry, but it does not have the same richness of color as the Pulsifer Quarry apatite.

Courtesy Judy Dawson

Quarry Finds

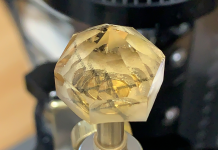

Small-scale mining has been done periodically in recent years at the Western Quarries, including the Pulsifer. While no apatite was found between 1996 and 2022, the Pulsifer Quarry was not entirely unproductive. In 2007, the “Stuck Steel Pocket” was found. It consisted of several large beryl crystals embedded in quartz. Though fractured, these crystals yielded several thousand carats of gem-quality aquamarine.

The Pulsifer Quarry, like the other quarries in the region, has a “garnet line” or “garnet seam.” This is an almost continuous layer of almandine crystals a few feet above, and parallel to, the lower side of the pegmatite body. Most of the garnets in the seam are under a centimeter and are generally not gem quality. Below the garnet line, the formation consists mostly of graphic granite.

Above the line, it consists of blocky feldspar, quartz, mica books, and sometimes, pockets containing well-formed crystals, such as apatite. On one wall of the Pulsifer Quarry, the garnet line dips, indicating a thicker zone of coarse pegmatite, which seemed more likely to contain pockets. It was in this area that activities were concentrated in 2022.

Courtesy Tony Wielkiewicz

A Personal Account

Dudy Groves, in addition to mining at the Pulsifer Quarry, built the Poland Mining Camps, located in the town of Poland, Maine, not far from Mt. Apatite. He envisioned the Camps as a place dedicated to amateur rockhounds. Mary Groves continues to operate the Camps today.

Mary does not operate the Camps by herself. She has many friends and family members who help. Tony Wielkiewicz conducts mining operations at Mt. Apatite, including drilling, blasting and excavator work. In 2022, he was assisted by Tom Derocher, while Tom’s wife, Kim Derocher, helped recover specimens and feed everyone. Also helping in 2022 were longtime rockhound guides Dan Namowitz, David Bechtel and Gary Bucklin.

Dan and David assisted Tony in all phases of mining, while Gary documented the new find. Later in the season, experienced miner Cal Birtic also lent a hand. My association with the Camps has evolved over many years from customer to part-time helper. My role in the present operation was to serve as an extra pair of eyes and to write about the discovery.

It should be noted that the current mining venture at the Pulsifer Quarry is not a part of Poland Mining Camps’ regularly scheduled collecting trips. In this case, given the considerable expense involved, ownership of most specimens is being retained by the Camps.

I was at the site for parts of August and September of 2022. In August, Tony conducted several small blasts to remove rock above the zone in which he thought pockets might occur. Increasing mineralization could be seen, including bluish cleavelandite, large muscovite mica books, black tourmaline and small amounts of lepidolite. On August 8, following a blast, I spotted a cluster of large beryl crystals in the newly exposed rock. It had been fractured by the blast, but I was able to recover most of it, and later reassembled a fair portion of it. While not gem quality like the Stuck Steel Pocket, it made an interesting large specimen, 28 cm long, weighing about 4.5 kg.

But it was not common beryl that everyone wanted. It was apatite. On August 10, I was picking through some rocks from a recent blast when something caught my eye – aglint of purple. I picked up a small piece of cleavelandite. Checking under a loupe revealed a small (3 to 4 mm), broken bit of apatite, the first one seen at the Pulsifer in 26 years. I held it up and said, “We have purple!” It was clear that Tony was heading in the right direction.

Courtesy Dan Namowitz

Significant Finds

The first complete apatite crystals, dozens of them, were found on August 13. Mary’s grandson and his girlfriend were there that day and dubbed the zone “Lucky 13.” The name stuck. A number of small pockets containing apatite were opened during the next few weeks. Some pockets were lined with deep yellow muscovite crystals, while others were openings among blades of cleavelandite or quartz crystals. Any of these minerals could serve as a matrix on which apatite crystals could be found, while other apatite crystals were found free of matrix.

A pleasant surprise was a large gahnite crystal. Gahnite is an uncommon member of the spinel group, consisting of zinc aluminum oxide. This crystal is a dark blue-green octahedron measuring about 5 cm across. The nearby Hole-in-the-Ground Quarry is famous for gahnite, but crystals from that quarry usually have a distinctive brown micaceous coating, which the specimen from the Pulsifer Quarry lacked. A few additional smaller specimens were also recovered.

Another interesting find was a pod of pink lithiophilite about 20 cm across. A phosphate mineral, it was recovered with great delight by Jim Nizamoff, a geologist who specializes in phosphates. He came to the quarry from time to time with permission to collect Also found was a pocket containing smoky quartz crystals, along with a few apatites and cookeite stained by manganese. That pocket was roughly tubular, and extended some 30 to 40 cm. A number of quartz crystals up to 15 cm long, some with complexly crystalized faces, were recovered.

The last large smoky quartz crystal from the pocket was firmly attached to the pegmatite. During work to recover it, ground water was seeping from the rock face. Initially, the water ran perfectly clear. After a little more probing, however, dark reddish-brown water began to ooze out of the face near the crystal. This was manganese-rich material often found in pockets containing apatite. The quantity of manganese material that oozed out indicated that there could be a number of additional pockets nearby. Sure enough, the next week, some very nice specimens of apatite on matrix were found in that area.

Courtesy Bob Farrar

Future Prospects

Work at the Pulsifer Quarry continued into early October. Over two months, hundreds of good specimens of apatite were recovered. Also recovered were dozens of smoky quartz crystals, the gahnite, the lithiophilite, some minor spessartine and a few minor pieces of beryl.

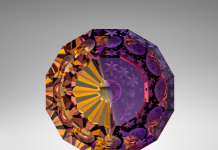

The apatite crystals found at the Pulsifer Quarry in 2022 range in size from under 1 mm to about 10mm. Though not as large as some found in the past, many of the new pieces are particularly fine. They exhibit a range of shades of purple, including many that can be considered royal purple. However, a few blue crystals, a rare color at this locality, were also found. The apatite crystals often show complex crystal habits. Some, for example, are 12-sided, rather than the usual six-sided habit. Many of the crystals could be considered gem quality. However, these crystals are absolute jewels as is.

Additional work at the Pulsifer Quarry is planned for the summer of 2023. The mineralized zone was not exhausted before mining was paused for the winter. Given what was found in 2022, expectations are high for additional fine specimens of apatite and other minerals.

This story about apatite previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Bob Farrar.