By Steve Voynick

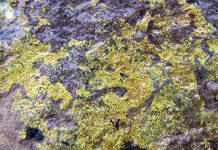

In mid-June, Hawaii’s Kilauea volcano was reported to be “raining green gemstones.” The internet carried images of green crystals that local residents were supposedly collecting by the handful, making the Kilauea eruption sound like a rockhound’s dream.

But geologists from the United States Geological Survey and the University of Hawaii quickly stepped in with a more sobering assessment. The crystals, they said, are olivine, a common mineral component of all Hawaiian basalt, and cannot be considered as gemstones.

Olivine Group Makeup

The olivine group consists of eight minerals, the most familiar being forsterite (magnesium silicate, MgSiO4) and fayalite (iron silicate, (FeSiO4). These minerals are end members of a solid-solution series based on the mutual substitution of iron and magnesium.

Technically, forsterite becomes fayalite when the weight of iron exceeds that of magnesium. Because intermediate members can be difficult to distinguish, all members of this series are collectively referred to as “olivine.”

Olivine crystallizes in the orthorhombic system and exhibits a limited range of colors. Because iron is present throughout the series, these colors range from deep brownish-green to very pale green.

Get the scoop about the latest rock, gem, and mineral features and news, rock shop and rockhound profiles, and exclusive freebies and promotions in your inbox. >>>

Balance of Iron Presence is Critical

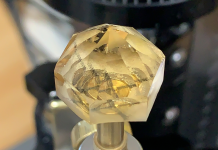

Transparent olivine with a bright, lime-green color is the gemstone peridot, which has an iron content of roughly 15%. From the gemological perspective, the amount of iron present is critical. Too much iron creates brown tones that detract from the brightness of the green; too little weakens the color intensity.

Some olivine occurs in metamorphosed limestone, sometimes as striking peridot crystals; most, however, forms at depths of at least 25 miles in the high pressure and temperature of the Earth’s upper mantle. It is transported to the surface in volcanic eruptions of deeply sourced mafic and ultramafic magmas that are deficient in silica and rich in iron and magnesium. These magmas solidify into basalt, basaltic pumice, or similar dark, extrusive rocks.

With its high crystallization temperature, olivine is one of the first minerals in magma to crystallize. Kilauea and other Hawaiian volcanoes extrude lava that is often a slurry of olivine crystals in magma.

Kilauea’s Identity

Kilauea, a shield volcano on Hawaii’s Big Island, is located directly over the Hawaiian

Hotspot, an area where magma from the mantle rises into the crust. Because shield volcanoes extrude fluid lava flows, they have characteristic, low, rounded profiles. At 600,000 to 300,000 years old, Kilauea is a very young volcano; it rose above sea level only about 100,000 years ago. It is also extremely active.

Its magma chamber, which is just three to six miles beneath the surface, draws magma from much greater depths where olivine crystals have already formed.

Geologists explain the “green gemstones” at Kilauea by theorizing that some olivine crystals separated from the magma as it erupted into the air. Most, however, seem to have weathered free from older basalt formations and simply had not been noticed previously.

‘Hawaiian diamond’

Common throughout Hawaii, olivine is known as “Hawaiian diamond.” One prominent source is Oahu’s famous Diamond Head landmark. Another is the Big Island’s Papak’lea Beach, one of only four olivine beaches in the world. This beach formed when wave action washed away the other components of weathered basalt and pumice, leaving behind a concentration of denser olivine crystals.

For a silicate, olivine is not particularly stable, but slowly decomposes on contact with water and carbon dioxide. Although the olivine currently on Papak?lea’s green beach will eventually decompose, it will be replaced by new olivine that weathers free from nearby basalt and pumice formations.

Some Big Island residents suggest that the “gemstones” are gifts from Pele, the ancient Hawaiian goddess of fire, lightning, wind, dance, and volcanoes, as an apology for Kilauea’s recent unruly behavior.

But geologists are not impressed with Pele’s gift, saying that, while some olivine crystals do have a lime-green color like peridot’s, most are too small, too fractured, and too lacking in transparency to be cut into gems.

Author: Steve Voynick

A science writer, mineral collector, and former hard rock miner, he is also the author of many references including, “Colorado Rock Hounding” and “New Mexico Rockhounding.”

A science writer, mineral collector, and former hard rock miner, he is also the author of many references including, “Colorado Rock Hounding” and “New Mexico Rockhounding.”