By Steve Voynick

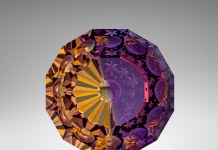

Of the 42 minerals that contain molybdenum as an essential element, most collectors are familiar only with wulfenite and molybdenite. Wulfenite (lead molybdate, PbMoO4) crystallizes in the tetragonal system as thin tabs with a diagnostic, bright-orange color.

Molybdenite (molybdenum disulfide, MoS2), the only ore of molybdenum, crystallizes in the hexagonal system as opaque, distorted tabs and dark-bluish-gray masses with a metallic luster and a telltale greasy feel.

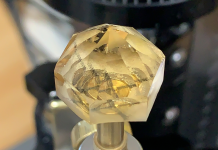

Much less familiar is molybdenum itself, which does not occur free in nature. Pure molybdenum is rarely, if ever, seen in its metallic state. Nevertheless, it is an important industrial metal with an interesting history.

Molybdenite’s Own Identity

Molybdenite, with its dark color, metallic luster, and greasy feel, was long confused with graphite and galena. The ancient Greeks called both lead and galena molybdos, using that word and molybdaina for all similar minerals and metals. Even as late as the mid-1500s, Georgius Agricola (Georg Bauer), in his de re Metallica, the most enlightened mining treatise of its time, referred to both graphite and galena as “molybdenum.”

It wasn’t until the mid-1700s that chemists finally distinguished graphite, galena, and molybdenite. In 1778, Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele showed that molybdenite was the sulfide of an unknown metallic element that he formally named “molybdenum.”

Four years later, Scheele’s colleague Peter Jacob Hjelm isolated elemental molybdenum as a heavy, dark powder that could not be fused into a cohesive mass for metallurgical study. At the time, molybdenum, which was assumed to be rare, was a laboratory curiosity with neither use nor value.

Confusion about molybdenum and molybdenite lingered for another century. Even after a prospector discovered an enormous molybdenite deposit at Climax, Colorado, in 1879, 15 years passed before chemists correctly identified his samples.

Mysteries of Molybdenum

French and German metallurgists began unraveling the mysteries of molybdenum in the

early 1900s. It is a silver-gray metal nearly as dense as lead, but much less common. Its two most notable properties are a melting point of 4,730° F. (2610° C.), which is 2,000° F. higher than that of most steels, and a pronounced ability to impart toughness, durability, and other desirable qualities to steel.

When World War I erupted in 1914, Germany unexpectedly revealed an arsenal of superior weaponry and armor. British analyses of captured weapons showed that the new German steels were alloyed with molybdenum, then obtainable only from a single, small deposit at Knaben, Norway.

Backed by soaring wartime demand for molybdenum as an alloying metal, miners rushed to Colorado to develop the Climax Mine in 1917. The greatest molybdenite deposit ever discovered, Climax has since yielded well over one million metric tons of molybdenum and is still producing today.

Copper Mining Connection

Because copper and molybdenum share a mineralogical affinity, many copper-sulfide ores also contain small amounts of molybdenite. In the 1970s, rising molybdenum prices led to the installation of molybdenite-recovery circuits in the concentrators of open-pit copper mines in the United States, Mexico, Peru, and Chile.

Today, most of the 235,000 metric tons of molybdenum mined worldwide each year are recovered as by-product of copper mining. China is the leading producer, followed by Chile, the United States, Peru, and Mexico. Molybdenum is one of the very few metals in which the United States is self-sufficient.

Today, molybdenum (as contained in oxide) sells for about $8 per pound. Ninety percent of all molybdenum is alloyed with steel to increase durability, toughness, wear-and corrosion-resistance, and overall strength. Although molybdenum does not harden steel per se, it enhances its ability to accept the hardening qualities of tungsten, manganese, and other alloying metals. Molybdenum compounds serve as pigments, lubricants, and catalysts, and are becoming increasingly important in “green technologies,” notably in the manufacture of solar panels, wind turbines, and biofuels.

Today, molybdenum (as contained in oxide) sells for about $8 per pound. Ninety percent of all molybdenum is alloyed with steel to increase durability, toughness, wear-and corrosion-resistance, and overall strength. Although molybdenum does not harden steel per se, it enhances its ability to accept the hardening qualities of tungsten, manganese, and other alloying metals. Molybdenum compounds serve as pigments, lubricants, and catalysts, and are becoming increasingly important in “green technologies,” notably in the manufacture of solar panels, wind turbines, and biofuels.

All of which is something to ponder when you next admire your prize specimens of wulfenite and molybdenite.

Author: Steve Voynick

A science writer, mineral collector, and former hard rock miner, he is also the author of many references including, “Colorado Rock Hounding” and “New Mexico Rockhounding.”

A science writer, mineral collector, and former hard rock miner, he is also the author of many references including, “Colorado Rock Hounding” and “New Mexico Rockhounding.”