Editor’s Note: This is the first in a two-part series.

By Bob Jones

I always wanted to go to Russia to see the Hermitage, the Fersman Museum and so many other wonderful and famous Russian sites. I got there when I was asked to participate in a video on Russian gems sponsored by Ocean Pictures and involving the University of Moscow. I quickly agreed. The plan was for me to go to Russia and visit all the museums and collections in Moscow and Saint Petersburg then I was to come home and write a script, submit it for editing then go back to Russia and be the on-camera host for the video to be shot on site. That was the easy part because I knew the script.

Carol and I made the first trip in April 1996. Winter had not ended and because we live in the Arizona desert we did not enjoy the cold. But we really had a great time. Carol shopped and we both were in awe of the gorgeous lapidary art in the great palace halls. In Moscow, we visited the Fersman Museum, the Vernadski Museum, the GEMS Museum, the University of Moscow Museum and the Kremlin and its museums.

Special Sites to See in Saint Petersburg

After Moscow we took the train to Saint Petersburg. The train ride was an adventure deserving of a separate column. In Saint Petersburg we had a special tour of the Hermitage, Saint Isaac’s Cathedral, the Peter and Paul Fortress and the research center at Saint Petersburg University School of Mines.

Each of these places was wonderful to visit and, like most tourists, we were amazed by the Hermitage and its phenomenal lapidary art as well as its treasures. Fortunately, we entered through the back doors of the Hermitage and saw things not on public display. Our Hermitage host was the Curator of Antique Cameos, who opened his vault, took out ancient cameos never displayed in public and showed them off. In fact, we were told he never allows anyone to handle his cameos, but he was so impressed with Carol he kept handing her rare, centuries-old Greek and Roman cameos including the famous Gonzaga cameo circa 300-200 B.C. to enjoy.

From his office he escorted us into the main halls to admire a most remarkable museum. Hanging on the walls in one gallery were original paintings by great artists like da Vinci. The paintings were not behind glass and you could actually touch them if you dared. We did not.

Visiting the School of Mines

That first trip gave me the information I needed to go home and write the script. I submitted it to Ocean Pictures and the University of Moscow, where I stayed on my second trip, which I did without Carol as it was a working trip to shoot the video.

My second trip to Saint Petersburg took me to the School of Mines. Along with studying

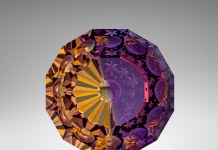

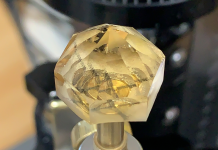

their mineral collection, I had a chance to meet the young lady who, while doing research in Siberia, discovered the first outcrop of charoite. I doubt there is a lapidary in the world who does not know about, admire and want to work with charoite. It is a most gorgeous violet-hued rock. That’s right, rock. We call the violet-hued material charoite but in actuality it is a rock made up of some 13 different minerals that together create a most beautiful multi-colored and patterned lapidary stone. The vivid violet color is derived from charoite, the stone’s dominant mineral.

The initial discovery of charoite was made deep in Siberia in areas that is a three-day overland hike from Lake Baikal. It is so remote, there are no trails or roads, only a river a day’s hike away. Ocean Pictures had actually planned a second government-sponsored video that would have taken us to the charoite deposits. But the government cut the money from the budget and we never made that shoot.

What is interesting is the story behind the discovery of charoite. It is not a common gem on the market but not because it is scarce. At last count, more than 25 different known outcrops of this valuable stone have been found in Siberia. Transportation is the problem. The cost of harvesting and transporting this beautiful rock in quantity is prohibitive.

It is also interesting to note that the lady scientist who first researched the charoite discovered evidence of two new minerals in the rock. She did not get credit for that discovery because her boss took over the project and claimed the discovery.

Exploring Russia for Rhodonite

Rhodonite, a lovely pink and black manganese rock, is another example of a colorful lapidary rock found in quantities in Russia. You see it everywhere; in palaces, museums, underground stations, and churches. One example of a fine rhodonite object is in the main lapidary hall at the Hermitage. There is a free-standing rhodonite bowl resting atop a shapely rhodonite pedestal about 5 feet high.

The rhodonite is a lovely, rich red shot through with streaks and small areas of contrasting black manganese oxide. The bowl is a single piece about 3 feet across and perhaps 10 inches thick. It is ridged with a rounded lip and made of the finest rhodonite I have ever seen. The color of the rhodonite is a subdued rose color with the rich black manganese mineral in stark contrast. It is very impressive.

The rhodonite comes from the central Ural mountains and is quarried in huge blocks of the gem. In the Gems Museum there is a display of several gorgeous rhodonite objects. This Museum is a government facility with the mission of promoting Russian lapidary and stone building materials. You do not have to go to a Russian museum to see superb rhodonite. Russia’s underground subway stations are all decorated with gorgeous lapidary rock or inlaid intarsia scenes all done in colorful gemstones including one station paneled with huge slabs of rhodonite. The government purposely fully designed all the underground stations in beautiful lapidary art.

Below the Surface in Saint Petersburg

The subway stations in Saint Petersburg are almost scary. They are the deepest stations I’ve ever been in. Standing at the head of the escalator, you feel as if you are descending into Hades. To enter a subway car you pass through two doors, a huge metal watertight door and the car door. The huge metal door shuts behind you, sealing you into the car and tunnel. The purpose of these doors is to seal off any flood waters that gush into the subway tunnels from entering the subway station. If you are in the car when this happens, tough luck. Saint Petersburg is built on a swamp, so the water table is almost at ground level. If a flood breaks into the underground and floods the rail system, these doors seal off the tunnels allowing them to fill, but protecting the stations.

Another massive gem material, Kolyvan jasper, is in very common use. It is quarried in the

Ural Mountains. It is a lovely dark gray color with bright white contrasting patches and lines in it, which give it a salt-and-pepper appearance.

My introduction to Kolyvan jasper was in the Hermitage. Carol and I visited this amazing former palace, but we did not go through the tourist entrance. Our escorts were Mike Leybov, producer of the gem video I worked on, and Alexander Eveseev, a friend of the Curator of Antique Cameos. We were taken behind the public area to see what the public does not see. As we passed along the halls, I saw large blocks of this lovely gray-white stone in a work room. They did not impress me. But when we later wandered through the main gallery, we saw a huge Kolyvan jasper bowl free-standing the middle of the room. It was shaped from a solid piece of Kolyvan asper. The term “enormous” is no exaggeration. The bowl stood on a six-foot-high shaped Kolyvan pedestal. Balanced atop the pedestal was a single solid piece shaped into a shallow oval bowl. The bowl measured an astounding 11 feet from end to end and about 4 feet across. I can not even imagine the size of the original block of stone needed to cut such an object.

Story Behind the Stunning Specimen of Kolyvan

When this giant bowl arrived from the Czar’s lapidary shop in Ekaterinburg, there was a problem. The block of jasper was cut on site and was estimated to weigh 40 tons. To haul it from the quarry in the Ural Mountains to the Czar’s lapidary factory in Elaterinburg required 90 horses and 50 men and took six weeks. The trip from there to the Hermitage was just as agonized and difficult. Once the bowl was finished, it was moved to the Hermitage by barge in a series of connecting rivers and canals until the pieces were ready to be taken into the Palace, and that’s when the real problem arose.

Besides the immense weight of the bowl, it was so large there were no doorways wide enough to shift the piece into the main hall with room for the mechanical retinue needed to move it. To solve the problem the workers simply tore open the side wall of the palace to make room for the bowl, its cradle and equipment to move into the palace and install it where it stands today for all to see. Only in Russia!

This huge Kolyvan jasper beauty was not the only example of the jasper in the Hermitage. One of the side dance halls had a lovely fireplace at one end of the hall and it, too, is done in Koluvan jasper. Incidentally, residing in that fireplace was a very colorful round trunk section of Arizona petrified wood.

Jasper in the Tombs

Another amazing example of Kolyvan jasper is in the Peter and Paul Museum, where all the czars and czarinas are buried. Each royal tomb in floor vaults is topped by a huge solid block of stone, not an ordinary stone of granite or marble, but is a stone shaped from a colorful valuable lapidary stone like rhodonite or Kolyvan jasper. I was not allowed to photograph these stone blocks but was told the Kolyvan jasper weighed 7 tons, enough to discourage a grave robber. Such a huge block would keep a lapidary happy for decades.

In the Hermitage is a most remarkable example of Russian inlay skill, a huge wall map of

Russia done completely in gemstones. The map won the gold medal at an International Exposition in France in the 1930s.

Certainly every rock hound and lapidary is well aware of Russia’s cutting grade malachite. Lovely objects of art, doors, wall panels and even furniture made of malachite reside in just about every royal palace and stately home.

They are all blessed with superb creations of what seem to be solid objects of bright green banded malachite created by Russian artists. The Czars used such objects as gifts when visiting royals and dignitaries of other countries. But did you know all those objects are not solid? Part II will explain that and continue to describe Russian lapidary stones.