By Bob Farrar

It’s what every crystal miner dreams of, that big pocket, the mother lode. The Brazilians have a word for it: bamburro. But such finds don’t only occur in Brazil.

As I recently learned, a new find of vanadinite in Morocco certainly qualifies as a bamburro, and it has resulted in a whole new mining rush.

I have had the opportunity to travel to Morocco several times in recent years and to visit some of the country’s many famous mineral and fossil localities. Regular readers of Rock & Gem may remember some of the articles that I have written describing some of these sites. Among these articles was one published in the May 2011 issue in which I related the story of a mining rush for vanadinite that had occurred in Morocco around the year 2000. That article was based on a visit that I made in 2008, after the rush when most of the miners had moved on. I found that visit interesting, but I was disappointed not to have been able to experience the rush in person. Well, it has happened again, and this time I got to see it.

Since it’s unlikely that most readers will have a copy of the May 2011 issue of Rock & Gem handy, a brief review is in order. As on previous trips, this visit to Morocco was arranged by tour leader Sara Mount of Silver Spring, MD. In Morocco, Sara works with Adam Aaronson, and his brother, Aissa. In addition to serving as tour guides, the Aaronsons are in the fossil business and have developed connections with fossil and mineral dealers across Morocco. It is through their contacts that I am able to see many of the geological riches of Morocco. My most recent trip was in October of 2019. The spring and the fall are the best times to go to Morocco; the summer can be brutally hot, and in the winter can present heavy snow in the mountains.

Rockhounding Trips to Morocco

Morocco is an easy country to visit and is very safe for Americans. Direct flights from the US are available, and no visa is required. No vaccinations are required either. Biting insects and venomous snakes are few, though one should be careful picking up rocks as there could be a scorpion hiding underneath. The people everywhere are friendly, and I have never felt threatened in any way. I find the Berbers to be particularly welcoming.

The Berbers are the native people of Morocco. They constitute the majority of the population in many of the mining areas of Morocco, but particularly in Midelt and Mibladene, the area described herein.

Vandinite Specifics

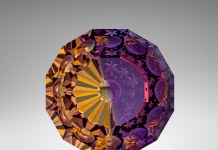

Vanadinite, because of its beautiful colors and interesting crystals, is a favorite among mineral collectors. It consists of lead chlorovanadate, Pb5(VO4)3Cl, and it crystallizes in the hexagonal system. Vanadinite is commonly a brilliant red to orange, but may also be brown, yellow, or, rarely, white. The arsenic-rich variety, endlichite, is usually brown to a silvery gray. Crystals are commonly barrel-shaped, but may also be short and tabular, and can be of “cavernous” or “hopper” form. Acicular, fibrous, and mammillary formations also occur.

The mineral is typically found in the weathered zones of lead deposits, most commonly in arid regions. A note of caution should be taken concerning storing and displaying vanadinite specimens – sunlight will cause them to turn dark and dull. As I mentioned in my 2011 article, small bits of vanadinite can still be picked up on the surface around the old workings. However, as they have been exposed to the sun for years, they are usually a dark, dull red, rather than the bright orange-red of fresh specimens. It is thus advisable to store vanadinite specimens in the dark, or at least away from direct sunlight.

Perhaps the most famous and prolific, vanadinite locality in Morocco, and indeed the

world, is Mibladen. Mibladene is located near the town of Midelt, about 144 miles southeast of Rabat (the capital of Morocco). Mibladen is a shadow of its former self during the heyday of lead mining. Midelt, though, is a thriving town that is the center of Morocco’s apple production. In addition, Midelt is the center of the mineral specimen market in Morocco. Besides vanadinite, one can see – and purchase – cobalt minerals from Bou Azzer, fluorapatite, and other minerals from Imilchil, and copper minerals from Kerrouchen, among others. Large numbers of specimens are shipped every year from Midelt to major mineral shows, such as Tucson and Munich.

Acif (ACF), the site of the mines described herein, is an area located between Midelt and Mibladene. Its name means “river” in the local Berber dialect. I have seen many vanadinite specimens at rock shows labeled as “ACF Mine,” I suspect that these are from Acif. These towns lie on a plateau between the High Atlas Mountains to the southeast and the Middle Atlas Mountains to the northwest. The elevation averages around 4000 feet, which makes it among the coolest parts of Morocco. The weather on my last visit was cool but pleasant. I have been there on other trips at the same time of year when we encountered rain and temperatures barely above freezing.

Morocco’s Modern Mining History

The formations in which vanadinite occurs at Mibladene are classified as strata-bound carbonate-hosted deposits. The term “Mississippi Valley-type deposits” is sometimes used to describe these areas. The host rocks consist of limestone of the lower Jurassic age. Galena is the main ore mineral, while barite is the main gangue mineral. Other secondary lead minerals found at Mibladene include cerussite and, rarely, wulfenite. Vanadinite crystals are often found growing on a matrix of barite, but can also be found on the country rock. Large scale mining for lead began at Mibladene in the 1930s. Commercial mining ended in 1983, and the mines have been officially closed since.

As I described in my 2011 article, pockets of vanadinite valued in the tens of thousands of dollars had been found only six to 12 feet below the surface. By the time of my visit, though, the shallow deposits at Acif had played out, and most of the miners had moved on. Only a few hard-core miners remained in the area, exploiting deposits in an old underground lead mine, with occasional success. Among these hard-core miners were two Berber brothers, Hmad and Lahrou, whom I have gotten to know over the years. They serve as Sara’s local guides to the vanadinite mines, as well as agate and copper deposits in the Midelt area. They were featured prominently in my previous article, and in others that I have written.

Most people thought that this region was largely mined out, with little prospect for significant additional production. Not so. Acif is back. It all began in February of 2019. A miner sunk a shaft, or “well,” to a deeper level, about 60 feet down, a few hundred yards from the previous site. There he hit a pocket of vanadinite that can only be described as colossal. It was roughly chimney-shaped, with side passages branching off. No one could give me exact dimensions, but it is said to have been big enough for eight people to sit within.

Not only was it a huge pocket, but the vanadinite that came out of it was also of particularly fine quality. The crystals were deep orange-red, sharply formed, and of unusually large size. Many of the crystals were up to an inch across, which is large for vanadinite.

Mining Practices

It took about four months to empty the pocket. At the time of my visit (October of 2019), sales of this material had brought in some $2,000,000 (US), with more material waiting to be sold. Word of the new find soon got out. In no time, a whole new mining rush ensued. Hmad and Lahrou have long had a small hut in the area, where they sleep, while mining. Their hut is made of rock walls about four feet high with a roof of bamboo and plastic sheeting. It measures about 15 feet across and contains beds and a small gas burner for cooking and making tea. A few other miners had similar shelters. There is now a small city of huts. There are some 500 – 600 huts, each housing perhaps four people, with individual wells. There are now at least 3,000 people mining for vanadinite, many of whom have no experience mining.

This is the very definition of “artisanal mining.” Artisanal, in everyday parlance, has a positive connotation, and usually refers to high-quality products made in small quantities (e.g., “artisanal cheeses”.) Artisanal mining, however, is often a negative term that refers to any small, often illegal, usually dangerous, mining operation, including so-called “blood diamond” mining. Most artisanal mining focuses on industrial minerals, such as cobalt, tin, gold, tantalum, and diamonds. In some countries, thousands of people labor under miserable conditions to recover these commodities, with middlemen taking most of the profits. For more on artisanal mining and the problems associated with it, see the article by Steve Voynick in the May 2019 issue of Rock & Gem.

Vanadinite mining at Acif is indeed illegal. However, the laws are rarely enforced, as long as the miners do not use explosives. It is recognized that vanadinite mining provides an economic boost to the area. Unlike artisanal operations in some countries, miners work for themselves and keep the profits. I wonder about safety issues, though. I did not see much in the way of safety equipment, such as hardhats or respirators.

Navigating On-Site Operations

Hmad and Lahrou have adopted new mining techniques. Instead of going down hundreds of feet in the old lead mine, they have sunk their own well. They go down about 60 feet, then dig laterally, as there is no ladder used to descend. To get down to the bottom of the well, a person wraps a rope around their legs and is lowered with a hand-cranked winch. Hmad demonstrated the technique. They offered to let me try it, but I declined.

In addition, theft is also a problem at the mine area, so Hmad and Lahrou had installed a locking door on their well, as well as on their hut.

In terms of mining, Lahrou and Hmad had not had much success when I visited.  However, they did have a nice lot of vanadinite that Adam Aaronson said came from the big pocket. The crystals included some sharp, tabular hexagons, as well as many complex hopper-grown crystals. Some pieces they referred to as “floaters” because there was no obvious point of attachment. There was no barite or other minerals associated with their vanadinite specimens, however. Thety showed me a freshly mined specimen, as well. It had a thin coating of mud, which is easily removed.

However, they did have a nice lot of vanadinite that Adam Aaronson said came from the big pocket. The crystals included some sharp, tabular hexagons, as well as many complex hopper-grown crystals. Some pieces they referred to as “floaters” because there was no obvious point of attachment. There was no barite or other minerals associated with their vanadinite specimens, however. Thety showed me a freshly mined specimen, as well. It had a thin coating of mud, which is easily removed.

On-Site Situation

Along with the vanadinite, they recover galena. No good galena crystals are found; they sell it for a few cents per pound as lead ore. An interesting technique is used to provide ventilation in the underground workings. There is also no electricity on the site, so miners must either rely on generators, which are expensive or get creative.

For ventilation, a sheet metal duct is inserted down the well. The top end is bent 90 degrees. A bucket or small trash can with a hole in the bottom is attached to the upper end of the duct. The bucket is pointed into the wind and funnels air down the duct. The wind blows almost constantly in this area. In fact, the government is planning a wind farm nearby as a part of Morocco’s effort to replace fossil fuels with renewables.

Flooding can also be a problem on the site. Winter is the rainy season in Morocco, and Midelt may get enough rain and snow to flood the underground works. With limited equipment and no electricity for pumps, work usually stops until the tunnels drain.

Like mining everywhere, digging at Acif is a financial gamble. It can cost up to $2,000 (US) for tools and equipment to sink a well. Out of the hundreds of wells recently dug in the area, perhaps five have hit big pockets valuing over $100,000 (US). Most come up dry.

It’s hard to say how long the current mining rush will last. Undoubtedly, some people will get discouraged, or go broke and leave. But, if some people continue to find vanadinite, the rush may continue.

At least I was witness to this rush at its height, for which I feel fortunate. And who knows; there may be more bamburros waiting to be found.

About the Author: Bob Farrar is a writer and a longtime collector of minerals, fossils, and gemstones, and has traveled extensively in pursuit of the hobby. He is active in several Maryland clubs, and is a dealer at area shows. He holds a Ph. D. in entomology and is retired from the USDA in Beltsville, MD.