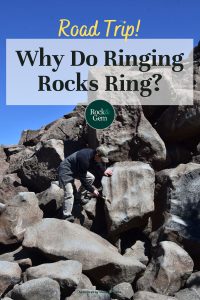

Why do ringing rocks ring? Everyone loves a mystery, especially when it sounds like a chorus of bells from civilization. Listening to the resonating “gong” after tapping one of Montana’s Ringing Rocks with a hammer is not only surreal, this seemingly inconspicuous pile of boulders inspires more questions than answers, even for geologists.

Discovering the Ringing Rocks

While the Ringing Rocks have been around longer than humans, according to a 1933 article in The Montana Standard, the earliest recollection of this area being “found” was when Butte local, R.T. “Kid” Ogle, heard a rock making a melodious tune as his boot hit one of them. Surprised, he tested other rocks with a pick, quickly realizing he stumbled upon a remarkable curiosity. Soon after his discovery, following in the footsteps of many pioneers of early tourism, Ogle led tours to what he dubbed “Ogle’s Volcano.”

Over the years, the land changed hands until the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) acquired the area in the mid-1960s, allowing public access, as well as ensuring that the unique rocks wouldn’t be mined for commercial use. Yet, even decades later, it’s one of those backroad secrets mostly only locals know.

Getting to the Ringing Rocks

The challenge, which is typical for Montana, is the area is not easily accessible. Although it’s only four miles from Interstate-90, the single-lane road is rocky, rutted and not where you want to be in the family car.

Visitors quickly notice that this is a popular area for motorbikes and ATVs, which are well-suited for the terrain. And while you can theoretically drive to the base of the boulders with a truck or high-clearance 4WD, thankfully, there are several places to pull out along the way for those who would rather walk than be jostled the entire way.

What’s equally interesting is the rocks themselves look like so many others in the Montana landscape. It’s not until you use your hammer or one of the hand-made versions hanging at the site, that your mind is blown. Ranging from a deep resonance to higher-pitched notes, few other rocks on earth sing like these.

Why do Ringing Rocks Ring?

Realizing that even ancient people sought out these rocks for their acoustic qualities raises the question, once again, about what causes this fascinating characteristic.

“It’s not so simple that there is one specific thing that makes them ring. There are several different factors. There’s still a lot to be figured out,” says Stuart Parker, PhD., a geologist with the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology. “It’s still pretty much an open question.”

Ancient Rocks

It’s no wonder rocks with these characteristics have been used for eons by ancient cultures. There is ample evidence of lithophones, where primitive cultures used these rocks to form an instrument dating back over 6000 years. There is even speculation that some of the stones of Stonehenge originated in the Preseli Hills area of South Wales, which is known for its ringing rocks, and were hauled 135 miles to this site specifically because of this characteristic.

Geology of the Area

Geology of the Area

Parker said the rocks developed because of magmatic intrusion. Called the Ringing Rocks Pluton, at one point magma rose from the depths, then cooled under the surface. One way to picture it is to think of them forming as an item from a forge, then cooling as one.

This entire area is part of the Boulder Batholith, formed in the late Cretaceous era.

Parker noted, “The Boulder Batholith is like the molten core of an old mountain belt.”

The signature representation of the Boulder Batholith is the rounded rock formations caused by the granite below the surface being pushed upwards during geological processes. Erosion wore them down into a smoother, almost egg-shaped appearance.

As for the Ringing Rocks, they were not uplifted like the Boulder Batholith. “These rocks were in the same space since they were made,” explained Parker. “One cool thing, if you are observant, there are very faint layerings to the rock. It was once a cohesive body of rock.”

This means that although the Ringing Rocks were put in place between 145 to 65 million years ago, it was the freezing and thawing action during the Pleistocene period, what we call the Ice Age, that brought to the surface what we see today.

Unlike the Boulder Batholith, they tend to be more angular and even flat at times.

And even though both the Boulder Batholith and Ringing Rocks were created around the same period, the Ringing Rocks is what’s called gabbro, an igneous mafic intrusive rock. Known for its hardness, gabbro is sought after for commercial purposes as black granite for countertops, along with its use in the mining industry.

The Ringing Rocks were considered for the construction of the Fort Peck Dam during the push for projects during Roosevelt’s New Deal program. In the early 1960s, a mining company sought to purchase them to grind up for use in sandblasting.

What’s equally fascinating is when the area is viewed on a geological map, the fairly circular 160 acres look like a bullseye with concentric circles of different rock types. Granite and granite porphyry is found in the center, while the next layer is quartz monzonite. Beyond that, layers include amphibole biotite monzonite, olivine pyroxene monzonite and amphibole monzonite. While these outer types are all mafic rock, their chemical composition makes them unique from one another, affecting how they weather over time.

Theories for Why Do Ringing Rocks Ring

All of this still doesn’t explain why the rocks ring. Some thought they were hollow, which they aren’t. Others claim it’s due to magnetic qualities. This is not the case, either. Some speculate that it’s because of iron within the makeup of the stones, but in reality, most only have roughly seven percent of this element. Plus, there are other rocks with far higher concentrations, which do not have this melodious characteristic.

Another hypothesis is the rocks create their sound due to how they are stacked upon each other. This leads to the belief that the rocks won’t ring if removed from the pile.

“I think it’s accurate, but it’s a bit misleading,” said Parker. “The key is to have the rocks suspended to resonate. They need to vibrate like a gong.”

Yet, as lithophones have been around for thousands of years they can be moved.

It might just be a matter of the proper suspension to allow the natural resonance to occur. (Of course, never remove these rocks from public lands to test this theory.)

Other Ringing Rocks

To add to the overall mystery, other ringing rock fields are found in Australia and Great Britain. Closer to home, rocks in Southeastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey share the same acoustical characteristics, yet have different compositions and environments.

Formed similarly, these are also mafic rock types akin to Montana’s pluton formation created as a magma intrusion, although the Pennsylvania formation is diabase, a volcanic basalt that is similar, but still different, to the gabbro of the Ringing Rocks.

Ron Sloto, a professor at West Chester University in West Chester, Pennsylvania, has studied the ringing rocks in his region for decades. He described their creation as, “Molten lava moving up and oozing between layers of rock, then cooling over years and years. When the diabase cooled, it cracked.”

These cracks, as well as general exposure to the elements further, enhanced spheroidal weathering. “It left a lot of boulders,” he said.

Pennsylvania Ringing Rocks

While this enormous diabase sill extends along the length of the Appalachian Mountains, and most of these rocks do not ring, several specific boulder fields have this melodious feature. Two of the most popular places to find them are Ringing Rocks County Park in Bucks County, which encompasses 7.8 acres, and Ringing Rocks Park near Pottstown. Developed in 1895, besides the amazing geology, the park is a favorite for families to picnic and enjoy their indoor roller rink.

There is also Stony Garden, located on State Game Lands #157, which is the largest boulder field extending roughly one-half mile long. The trail to this last option is less than a half-mile long on relatively flat and easy ground, although part of it walks through a marshy area and you need to maneuver over a few rocks to reach the ringing part of the boulder field. Sloto also noted that there are other fields scattered throughout the region with many of these on private land.

Although iron and aluminum make up part of this diabase, these elements still are not the reason for their voice. One thought concerning the reason the Eastern rocks ring is because of the extreme internal pressure created during their formation.

Sloto said he lives very close to a quarry where occasionally one of these rocks explodes when cut because of the release of this pressure. In an informal study by a professor at Rutger University, he discovered that “live” ringing rocks (ones that made a sound) measurably expanded, or relaxed, within 24 hours of being cut into slices.

This leads some experts to surmise that the sound is caused by these extreme internal stresses, but they still don’t know for sure.

Beyond the questions on why the rocks ring, some visitors seek out a paranormal aspect, particularly in the Eastern boulder fields. People note that even though forests surround the rocks, there is minimal to no bird activity and animals don’t travel across the rocks. And no vegetation grows among the stones. The mystery deepens.

Even though, or maybe because, we have no solid answers on the magic that allows these stones to sing, the ringing rocks throughout the United States and the world will always mesmerize us with their music.

This story about ringing rocks previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story and photos by Amy Grisak.