By Steve Voynick

In much of the world, the 1993 blockbuster movie “Jurassic Park” and its unending sequels have become synonymous with the word “dinosaur.” But in western Colorado, the word “dinosaur” is better associated with the town of Fruita and its surroundings.

Located ten miles west of the city of Grand Junction and not far from the Utah line, Fruita is a real “Jurassic Park” and a must-see destination for anyone interested in dinosaur paleontology.

An imposing, 20-foot-tall, forest-green dinosaur looming over the town square reflects Fruita’s pride in its paleontological heritage and history. This model, an accurate, life-sized depiction of Ceratosaurus magnicornis, a Tyrannosaurus-like predator, is Fruita’s official “town dinosaur.” Along with many other dinosaurs, its fossilized bones were found and excavated only a few miles away.

Showcasing Western Paleontological Remnants

Not to belittle Fruita’s town-square Ceratosaurus, but other nearby dinosaur-related attractions are far more impressive. Among them are an outstanding dinosaur museum, several paleontological research areas with hiking trails and interpretive signs, historic and active dinosaur-bone quarries, opportunities to accompany paleontologists on dinosaur-fossil digs, and even a national monument that showcases the region’s spectacular geology.

Fruita’s adventure with dinosaurs began in the late 1890s, shortly after a series of remarkable western fossil discoveries, mainly in Colorado and Wyoming, had transformed dinosaur paleontology from an obscure academic pursuit into an exciting and dynamic science with a large public following. These landmark discoveries had all occurred within exposures of the Morrison Formation, the sediments of which were laid down during the Jurassic Period some 160 million years ago.

Much of present-day Colorado was then a flat, low-lying coastal plain with sandy beaches, marshes, and tidal flats at the edge of the warm, shallow Interior Seaway. A tropical climate and profuse vegetation supported a booming population of both herbivorous and carnivorous dinosaurs. Varying sea levels, periodic flooding, and heavy sedimentation combined to quickly bury dinosaur remains in an excellent environment for fossilization.

In relatively recent geologic time, erosion exposed sections of the fossil-rich Morrison Formation. In western Colorado, the Colorado River cut deeply into the sediments to carve out the sprawling Grand Valley, the present site of Grand Junction and Fruita.

More Than Meets the Eye

In some areas, huge, intact, fossilized dinosaur bones protruded from hillsides in plain view. Native Americans flaked the abundant, well-silicified dinosaur bone into tools and points. By 1885, ranchers and sheepherders near Fruita had begun collecting “big bones” to sell as curios to railroad travelers or museums in the East. Several even made bone-hunting a full-time occupation.

But the true significance of Fruita’s profusion of dinosaur fossils went unrecognized until the arrival of a 31-year-old paleontologist named Elmer S. Riggs in 1900. Riggs had studied paleontology at the University of Kansas. By the 1890s, he was an assistant paleontologist at Chicago’s Field Columbian Museum (now The Field Museum) and participated in field expeditions to Wyoming and South Dakota.

After assisting in several major dinosaur-fossil recoveries, Riggs became determined to discover a new fossil field of his own. But rather than just randomly searching, he began instead by writing letters to a dozen communities near Morrison Formation exposures in Colorado and Wyoming, asking if residents knew of any fossilized-bone deposits.

Among those who replied was Dr. S. M. Bradbury, a Grand Junction dentist and president of the Western Colorado Academy of Science. Bradbury reported that dinosaur bones were common near Fruita and that their deposits had never been scientifically investigated.

Intrigued by Bradbury’s letter, Riggs asked The Field Museum to fund an expedition to western Colorado. Hesitant to risk funds on unproven bone fields, the museum directors offered only limited support—if Riggs himself would pay part of the expenses.

Countless Discoveries

Riggs agreed, and in May 1900, a group of residents welcomed him at the

Grand Junction railroad station. Eager to show off their discoveries, they took him on a tour of known fossil sites. Within days, Riggs recovered the fossilized shoulder bones and vertebrae of the large sauropod Camarasaurus.

His first major discovery came only weeks later southeast of Fruita on a low rocky hill that now bears his name—Riggs Hill, where he excavated the nearly complete skeleton of a Brachiosaurus, a huge sauropod new to science. Riggs’ Brachiosaurus, 30 feet tall and 80 feet from nose to tail, was then the largest dinosaur ever found. (An articulated, cast-replica mount of this specimen is displayed today at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport.)

Impressed with Riggs’ initial finds, the museum directors approved a return expedition the following year. They increased Riggs funding to $800, still very little for five months of equipping, feeding, and paying excavation crews, then transporting heavy dinosaur fossils by wagon and river raft to railroad freight depots for shipment to Chicago.

But this return expedition nearly ended before it began when a supply raft capsized, dumping its entire load of food and a ton of dry plaster (for encasing fossilized bones) into the Colorado River. Riggs considered calling off the expedition, but his local friends and supporters, including several serious amateur paleontologists, took up a collection to replace the lost food and plaster. During the following months, Riggs repaid their generosity with free lectures on fossil excavation and preservation and other paleontological topics.

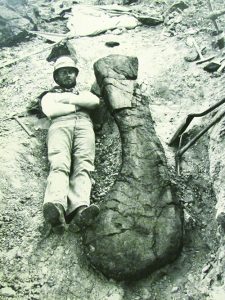

In 1901, Riggs recovered the rear two-thirds of a Brontosaurus (later Apatosaurus) from a site just south of Fruita, now known as Dinosaur Hill. Quarrying the deeply buried bones of this 70-foot-long sauropod from a steep hillside was no easy task. When removing the huge volume of overburden on the steep hillside became impossible, Riggs was not discouraged: He simply hired hardrock miners to tunnel into the hill to recover the bones from the world’s first and only underground “dinosaur mine.”

Giving Birth to Dinosaur Paleopathology

Riggs’ Apatosaurus skeleton included several ribs that had been broken, but then healed during the dinosaur’s lifetime—a discovery that pioneered the specialized field now known as dinosaur paleopathology.

By September, Riggs had collected six tons of plaster-encased dinosaur bones to ship to Chicago—but couldn’t pay the freight costs. This time his friends persuaded the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad to help out. The railroad shipped the bones free of charge as a gesture to the advancement of science. Several years later, when The Field Museum displayed the spectacular, full skeletal mounts of Riggs’ recoveries, Fruita gained international recognition as one of the world’s leading sources of Jurassic dinosaur fossils.

Riggs’ last year of field work at Fruita was 1903, but his local legacy lived on. In the 1920s, local amateur paleontologists who had learned from Riggs began making their own fossil recoveries. The discoveries of Al Look and Ed Faber attracted scientific interest from several western universities. Then, in 1937, when local fossil collector Ed Hansen found in situ vertebrae above Riggs’ original quarry at Riggs Hill, another local amateur paleontologist, high-school geology teacher Edward Holt, excavated nearly complete, fossilized skeletons of Stegosaurus, Allosaurus, and Brachiosaurus.

In 1937, Al Look, astutely foreseeing the potential of dinosaur paleontology to future area tourism, suggested preserving Riggs’ original bone quarries. The first step came the following year with well-attended dedication ceremonies at Riggs and Dinosaur hills. The guest of honor was none other than Elmer Riggs himself, then The Field Museum’s curator of paleontology and one of the world’s leading paleontologists.

Another local amateur paleontologist was Grand Junction attorney Ivan Kladder who, during the 1940s, excavated and amassed an extensive, well-cataloged collection of dinosaur fossils.

Museum Tends to It Origins

Elmer Riggs died in 1963, the same year that the Museum of Western Colorado was established in Grand Junction with dinosaur paleontology as its initial focus. Local amateur paleontologists provided the museum’s first fossil exhibits, including the entire Kladder collection.

Today, the Museum of Western Colorado, while greatly broadening the scope of its exhibits, has not forgotten its paleontological origins. In 2001, the museum opened a new exhibit facility in Fruita named Dinosaur Journey. Only two miles from historic Dinosaur Hill, it is dedicated entirely to dinosaurs and related aspects of paleontology and geology. Near the museum’s entrance stand colorful, near-life-sized models of a platy-spined Stegosaurus and a Ceratosaurus, the latter another tribute to Fruita’s official “town dinosaur.”

Interior galleries display the articulated casts of an 18-foot long Brachiosaurus forearm alongside photographic murals of Elmer Riggs and his crews at work in 1900. The largest of Dinosaur Journey’s eight full-skeletal mounts is a 50-foot-long Camarasaurus; the smallest is the predator Othnielosaurus, measuring just six feet from its nose to the tip of its slender tail.

Taking A Dino Journey

Dinosaur Journey also displays robotic dinosaurs that move, roar, and scream. These quarter-, half-, and life-sized models include such familiar genera as Tyrannosaurus, Stegosaurus, Triceratops, and Apatosaurus. Their realistic exteriors conceal interior aluminum frames, electric motors, and cam-operated shafts that impart motion to jaws, necks, forearms, and tails. A particularly dramatic model depicts Utahraptor, an 8-foot-tall, 20-foot-long “super-slasher” predator devouring the neck of a sauropod.

The roars and screams that echo throughout the museum are not random conceptions of dinosaur sounds. Drawing upon modern comparative anatomy and known dinosaur jawbone and neck-bone structures, paleontologists have modeled dinosaur vocal cords. The robotic dinosaurs’ roars and shrieks, specific to particular dinosaur genera, are based on sounds that actual dinosaur vocal cords would likely have made.

Locally recovered fossils are prepared for study and display in Dinosaur Journey’s working paleontological laboratory. The lab is staffed by professional paleontologists and volunteers who, time permitting, provide guided museum tours. Viewing windows enable the public to observe laboratory technicians working on locally recovered fossils.

One of the museum’s geology-related displays is fittingly called “Earthquake!!!” When visitors step onto a special floor section and press a button, they experience the simulated, but frighteningly strong, earth movements that would accompany a 5.3-magnitude temblor.

Making the Most of the Trip

Dinosaur Journey also distributes brochures and maps for the nearby field attractions—Dinosaur Hill, Riggs Hill, the Fruita Paleontological Area, and the Trail through Time. Dinosaur Hill, a few minutes south of Dinosaur Journey on Colorado Route 340, has a one-mile-long loop trail with interpretive signs. The hill’s summit offers panoramic views of Fruita, the Colorado River, the Grand Valley, and the canyons and spires of nearby Colorado National Monument. The trail passes the portal of the historic underground “dinosaur mine,” where a bronze plaque commemorates Elmer Riggs’ fossil recoveries 118 years ago.

In 1991, paleontologists reopened this underground mine where Riggs had recovered his Apatosaurus specimen—and recovered three Apatosaurus tail vertebrae that Riggs had missed.

Just a few miles from Dinosaur Hill is the Fruita Paleontological Area, 360 acres of deeply eroded badlands where fossils represent a greater diversity of Jurassic life than any other known place on Earth. Quarries here have yielded skeletons of such plant-eating giants as Apatosaurus, Camarasaurus, and Stegosaurus; the carnivore Ceratasaurus, and the two very small dinosaurs Echinodon and Fruitadens. A half-mile-long loop trail, marked by 20 detailed, illustrated, geological and paleontological interpretive signs, passes two historic dinosaur quarries, a dinosaur-track site, and a dinosaur-eggshell dig.

The Fruita Paleontological Area is also home to brightly colored collared lizards, some nearly a foot long. Males have blue-green spots and stripes, yellow-brown heads, sunflower-yellow forefeet and eyelids, and black collars. Although not descended from dinosaurs, collared lizards have a decidedly prehistoric look that adds to the interest of this paleontological area.

Riggs Hill, seven miles east of Fruita, has a three-quarter mile-long trail with interpretive signage that passes Riggs’ original Brachiosaurus quarry, now marked with a commemorative bronze plaque.

Modern-Day Discoveries

Fossil discoveries and excavations in the Fruita area continue today. In 1981, paleontologists Pete Mygatt and John Moore discovered an extraordinarily rich fossil deposit in Rabbit Valley 17 miles west of Fruita at Exit 2 on I-70. Today, this deposit is the Mygatt-Moore Quarry, a part of the Rabbit Valley Natural Research Area, which is jointly managed by the Museum of Western Colorado and the Bureau of Land Management. The quarry’s 1.5-mile-long Trail through Time features 21 interpretive geological and paleontological signs, and places where visitors can touch in situ fossilized dinosaur bones.

In late Jurassic time, Rabbit Valley was a silty watering hole where periodic

flooding created the conditions necessary for bone fossilization. The Mygatt-Moore Quarry has yielded more than 3,000 dinosaur bones, among them the nearly complete skeletons of the herbivores Apatosaurus and Camarasaurus, the carnivore Allosaurus, and the recently discovered armored herbivore Mymoorapelta (named after the quarry).

Just five miles south of Fruita, Colorado National Monument offers fascinating perspectives on the region’s dramatic geology. The rock exposures in this 36-square-mile tract of sheer-walled canyons, towering monoliths, and red sandstone cliffs represent a billion years of geologic time from the late Precambrian to the early Cenozoic eras. Views to the north and east across the Grand Valley and the Colorado River reveal the enormous extent of the erosion that exposed Fruita’s treasure trove of fossilized dinosaur bones.

Popular half-day, one-day, and five-day fossil digs at the Mygatt-Moore Quarry are open to the public on a fee basis. Scheduled by Dinosaur Journey throughout the summer months, these digs include transportation from the museum to the quarry, lunch, a special tour of the museum’s fossil-preparation laboratory, and hands-on, excavation work with instruction from professional paleontologists.

For a change of pace from the many paleontological attractions, visitors should consider the Two Rivers Winery on Colorado Route 340. Just a few miles from Riggs Hill and in the shadow of Colorado National Monument’s red cliffs, the Two Rivers tasting room offers an outstanding selection of varietal wines produced from locally grown grapes. It’s a fine place to contemplate the rich paleontological heritage of Fruita’s “Jurassic Park.”

Fruita is located just off Interstate 70 at Exit 19, 10 miles west of Grand Junction, and 19 miles east of the Utah line. Dinosaur Journey is a half-mile south of Fruita on aptly named Jurassic Court. The museum is open daily; hours vary seasonally. For further information, contact Dinosaur Journey at 970-858-7282 or visit www.dinosaurjourney.org.