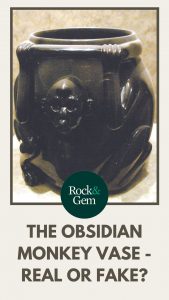

The Obsidian Monkey Vase is located in the Mexica (Aztec) Room in the National Museum of Anthropology (MNA) [Museo National de Anthropología] in Mexico City. This is the largest and most visited museum in Mexico, renowned for preserving Mexico’s indigenous legacy.

Obsidian Blades and Artifacts

What is obsidian? It is a natural hard volcanic glass that was used as early as 2,500 BC for arrowheads and ceremonial blades.

There are many obsidian carved blades and artifacts within the museum collections. On exhibit are natural obsidian nodule cores and long blades knapped off the nodules.

Obsidian was brought into the ancient city of Teotihuacan. This is where the famous monumental Pyramids of the Sun and the Moon are located, just outside today’s Mexico City. It was worked at the obsidian stone workshops in Teotihuacan and was made into blades and eccentrics (non-tool forms). These were to be used in everyday life and ceremonial affairs and were valued for their sharp edges.

What is the Obsidian Monkey Vase?

The Obsidian Monkey Vase is considered a masterpiece of Aztec stoneworkers. The vase is reportedly from Texcoco, a city and municipality in the State of Mexico, 25 km northeast of Mexico City. Texcoco was a major Aztec city on the eastern shores of Lake Texcoco, south of Teotihuacan.

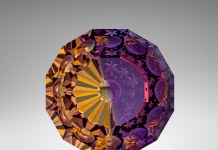

The Obsidian Monkey Vase is featured under the Mexica collections (catalog number 11.0-03514). It is a vessel made from a singular piece of obsidian, measuring six inches tall. The vase is finely carved and polished to a mirror finish. It depicts a stylized charming little monkey holding its tail with both hands, believed to be a representation of a spider monkey. In the museum’s 2010 printed guide, the photograph legend calls it a pregnant monkey.

Per the museum’s exhibition label, “the monkey is associated with the Ehécatl-Quetzalcóatl deity, as well as black rain clouds.” The wind was one of the original elements that participated in the creation of the universe. It was the domain of Ehécatl-Quetzalcóatl, the snake-bird deity, identified by a mask in the shape of a beak that covered the lower part of its face. The people believed the god produced the wind by breathing through this mas. He was able to give life to the planet earth. He is also associated with spider and howler monkeys.

Stolen Items

This Obsidian Monkey vase was among 124 items stolen from the National Museum of Anthropology on Christmas Eve 1985 (NY Times, Dec 27, 1985). It was miraculously recovered three years later and returned to the museum (LA Times, June 15, 1989).

The Obsidian Monkey vase was mentioned in the museum’s first catalog in 1882.

The National Museum

The vessel came to the National Museum in 1880 and was cataloged as having come from an ancient tomb. It was sold to the MNA by a doctor named Raphael Lucio in 1876 (catalog item #127 of Vol. II), who had acquired it through one of his patients, originally found at a hacienda near Texcoco. The story is told by French collector and archeologist Eugène Boban (1834-1908), who saw the vase at Lucio’s house, and who may have done the appraisal (ibid. Walsh, 2004). The obsidian monkey vase was photographed while at the doctor’s office. From there three engravings were produced and illustrated Eugène Boban’s article published in 1885 in the journal Revue d’Ethnographie.

When Boban began negotiations to sell part of his collection to the Smithsonian, he corresponded with curator William Henry Holmes (1846-1933), about fakes and counterfeiters. Boban shared his knowledge of Mexican lapidaries who made fake antiques. He even named several forgers and concluded that “all obsidian objects with body, arms and legs can be considered fake.” (Smithsonian archives, SIA RU 7084, Walsh 2004)

Suggesting a Fake

Some suggest because Boban was aware of several fake obsidian vases and idols coming from the small town of San Juan Teotihuacan, that the monkey obsidian vase is a fake, too.

This supposition was presented by Marc Zender, from the Department of Anthropology at the Tulane University, at the 2016 Annual Maya at the Playa Conference. He alleges the obsidian monkey vase is also a fake. He pointed to the book Faking Ancient Mesoamerica (Nancy l. Kelker and Karen O. Bruhns, 2010) for additional examples of lapidary forgeries.

Could this beautiful vase be fake? How is it possible? It is still on exhibit at the MNA museum and promoted on their website as a masterpiece. This is the 21st century; wouldn’t they have identified all fake artifacts by now and have them removed?

The Obsidian Artwork Trail – Batres

Leopoldo Batres (1852-1926) worked as an archeologist and anthropologist for the National Museum of Archeology in Mexico City between 1884 and 1888. In his 1909 book Antigüedades, mejicanes falcificades, falcificaciones y falsificadores (Ancient Mexican fakes, forgeries and counterfeiters), Batres describes the obsidian lapidary industry of fake vases and figures. He states that “the counterfeiters worked the obsidian in a very simple style. They took a block of obsidian and carved it with oil and emery. They carved it by means of sharp punches and chisels of well-tempered steel, roughing the piece by tapping with the chisel and mallet, and once the piece was modeled they polished it again with oil and fine emery dust.”

Batres says that “the Mexican National Museum has a very rich collection of fakes.” In the book, there is a huge number of illustrations of those fakes, including pottery pots and figurines painted black, gold pieces, bronze figures, alabaster masks and figurines, and obsidian objects and figurine idols from the 19th c., including several obsidian masks, discs and frogs, for which he said that, “the falsification of obsidian objects has reached a high degree of art, and that sometimes only a very expert eye can distinguish the fake”. However, the Obsidian Monkey vase is not among them.

The Obsidian Artwork Trail – Jones

Mark Jones, Assistant Keeper of the Department of Coins and Medals at the British Museum, curated the exhibition “Fake? The Art of Deception.” This opened in April 1990 at the British Museum with hundreds of fake artworks from all civilizations and several museums. Included were two Aztec-style obsidian masks featured in the richly-illustrated catalog. Jones says that “The late Gordon Ekholm, one of the foremost experts in the detection of Mesoamerican fakes, had warned that all large-objects of obsidian, especially masks, must be considered suspect” (Fake: the Art of Deception, Mark Jones, 1990). [sited, The problem of Fakes in Pre-Columbian Art, G.F. Elkholm, Curator VII/I, 1964, pp 19-32].

Jones continues, “It is, indeed, hard to think of any large obsidian mask among the known body of antiquities from Mexico that is generally accepted as genuine. Masks are, however, among the most sought-after categories of an object with collectors.” The two examples included in the exhibit – one of the rain-god Tlaloc and one of a man’s face – were “almost certainly nineteenth or early twenty century fakes.”

Authenticating Stone Artifacts

Authenticating stone artifacts is difficult. There is no test to prove the age of a stone artifact. Archeologists and anthropologists can only go by the iconography, artistic style, and choices of materials, matching documented artifacts. Systematic excavations of pre-Columbian sites did not begin until the late 1880s (What is Real? A New Look at PreColumbian Mesoamerican Collections, Jane MacLaren Walsh, Anthronotes, SI, Museum of Natural History publication, Spring 2005).

Interestingly, there is also a similar monkey vessel, carved in Mexican onyx marble (known as tecali) with pyrite and shell inlaid eyes and teeth, on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, at the Mesoamerican Gallery #358. This Mixtec culture vessel dates between the 10th and 13th centuries. This vessel is 7 ½ inches tall.

The Obsidian Artwork Trail – Walsh

Dr. Jane Walsh, PH.D., Anthropologist Emeritus of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History wrote a 2004 article La Vasija De Obsidiana de Texcoco (The Obsidian vase from Texcoco) published in Arqueologia Mexicana (Vol. 12, #70) about the history of the monkey vase.

Although Walsh has not examined the vase in person and doesn’t know anyone that did. She also said, “It may very well be a fake – Lucio also sold an obsidian mask to the museum – but it cannot be said with any certainty or accuracy without being tested”.

Dr. Walsh’s closing argument says that “any artifact removed from its original archeological context is devoid of any certainty regarding its cultural identity.” And that refers to any excavation discovery carried out without proper archeological study and precise documentation of each artifact’s location. The Obsidian Monkey vase was featured on the cover of Arqueología Mexicana (Sept-Oct 1996, Vol IV, #12) under the magazine’s title “Looting and Destruction”.

Obsidian Monkey Vase – Real or Fake?

The obsidian fakes produced in the 19th and early 20th centuries have a “primitive” look, supposedly reflecting the “crude” work of the ancient lapidaries, often imitating the much-older Olmec carving style. These fakes were reflecting the private collectors’ viewpoint around the world at the time who purchased these fakes and fueled the reproduction of artifacts. The starkness and austerity of ancient artworks is often mistaken as crudeness.

We can only trust one day we will know for certain if this beautiful Obsidian Monkey vase is a true Aztec lapidary masterpiece.

This story about Mexico City’s Obsidian Monkey Vase by Helen Serras-Herman appeared in the August 2021 issue of Rock and Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe!