Story and Photo by Steve Voynick

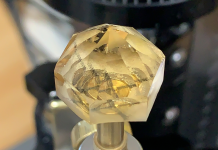

Among many mineral and crystal collectors, Arkansas is synonymous with quartz, and for good reason. More fine specimens of rock crystal—the transparent, colorless variety of macrocrystalline quartz—have come from west-central Arkansas’ Ouachita Mountains than from any other region.

Geologists trace the origin of the Ouachita Mountains back 600 million years to the development of a rift along the southern edge of the North American tectonic plate. A section of the crust separated, leaving behind marine basins that extended far inland. Massive deposits of silica-rich marine sediments then accumulated on the basin floors and eventually lithified into formations of sandstone and shale. Tectonic forces later thrust the separated section of crust back and beneath the North American Plate, uplifting these sedimentary formations thousands of feet to create the original Ouachita Massif.

Some 245 million years ago, silica-rich solutions began to circulate through this fractured sandstone and shale, precipitating large amounts of quartz in complex vein systems. Most of this quartz is of the massive, translucent, milky variety; smaller amounts are of rock crystal.

These quartz-filled veins are concentrated in a 30- to 40-mile-wide, 170-mile-long zone that represents the geologic core of the Ouachita Mountains. Erosion eventually reduced the surface of the Ouachitas to expose many of these quartz-crystal-filled veins.

Archaeologists have contextually dated the oldest known artifact made from Arkansas rock crystal, an arrowhead, to 9000 BCE. While exploring the region in 1541, Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto noted that many Native American projectile points were fashioned from quartz crystals.

In the first written report about Arkansas rock crystal in 1819, American geographer and geologist Henry Rowe Schoolcraft penned this fitting description: “… very pure and transparent, and beautifully crystallized in six-sided prisms, terminated by six-sided pyramids”. When Schoolcraft visited the Ouachitas, he found places where rock crystal literally covered the ground.

According to historical accounts from the 1860s, settlers in the region were collectively selling over $1,000 worth of crystals each year—a substantial sum at the time. In the 1870s, American mineralogist Dr. A.E. Foote (1846-95), head of the Philadelphia-based Foote Mineral Co., which was then the nation’s largest marketer of mineral specimens, hired crews to dig rock crystal in commercial quantities. And during the 1920s, the first paved roads in the Ouachitas brought a wave of tourists and a huge demand for crystals.

When World War II created an urgent need for electronic-grade quartz for use in chronometers, radios, radars, bombsights, and other instruments, the U.S. War Department designated electronic-grade quartz as a strategic material. Brazil was then the only source of electronic-grade quartz, but when German U-boats threatened the maritime supply from Brazil, the government turned its attention to Arkansas.

Backed by federal subsidies, miners and prospectors rushed to the Ouachitas. In 1943 alone, the government purchased 212,000 pounds (106 tons) of rock crystal, valued at $35,000. Only part of this production was electronic-grade quartz, but the remainder went to optical uses. Although Brazil ultimately continued to supply most electronic-grade quartz, Arkansas quartz nevertheless made an important contribution to the war effort.

The 1950s and 1960s brought increased automobile travel and growing interest in both mineral collecting and the metaphysical aspects of crystals. Amid soaring demand for Arkansas rock crystal, a host of rock shops and fee-collecting areas opened, most of them near the town of Mount Ida. By the late 1980s, 80 quartz-mining claims had been registered on federal land, and top-quality crystals were bringing $100 per pound.

The historic rock-crystal production from both federal and private land in Arkansas probably exceeds 1,200 tons (2.4 million pounds). And because only an estimated 5% of all the rock crystal that is thought to exist at or near the surface in the Ouachita Mountains has ever been collected or mined, there is still much more waiting to be found.