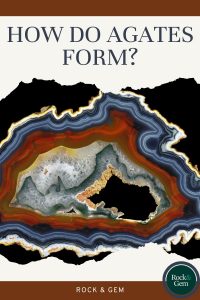

How do agates form? With so many variables including temperature, pressure and chemistry that can influence silicon dioxide as it forms, we may never have a single answer regarding agate formation.

Agates in Ancient Times

Ancient philosophers and scientists were puzzled over how agates originated. They wrote about them and began using them in various ways, even imbuing them with special powers. Through the centuries, attempts were made to explain where and how agates originate, and a host of theories developed unsuccessfully.

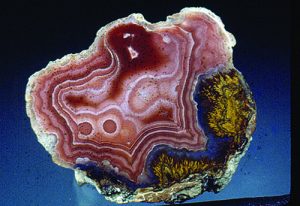

From archeological excavations, we know agates were in use at least 6,000 years ago as tools, weapons, and personal adornment. In the following centuries, philosophers in early cultures like the Sumers of Mesopotamia in the Near East and later Greeks and Romans tried to explain agates. Cultures in those ancient times cherished agates and used them in a host of ways. Eye agates were often endowed with special powers.

Agates in Greece & Rome

One of the earliest Greeks to write about agates was Theophrastus from the Greek Island of Eresos. We know about him because some of his writings survived. One book he wrote, in about 300 B.C. titled Peri Lithon, “On the Stones,” survived and described rocks and minerals.

As Rome emerged as a dominant force in the Mediterranean, agates played a vital role in their culture. The noted Roman writer Pliny the Elder, who died during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, wrote about agates in his Naturalis Historia. By this time, the name agate was thought to be derived from a known source, Sicily’s Achates River. Many thought this was the original agate source, but there is plenty of evidence to dispute that.

Agates were known long before in Egypt and the Near East. The island where Theophrastus was born produced agates several hundred years before agates were sourced from Sicily.

There is an excellent chapter in the two-volume set Agates Vol. I and II by Johann Zenz published by Bode, Hallern, Germany, about agate in ancient times.

Why So Many Theories?

Agates are found in numerous localities and in widely varying environments, which can influence their formation. Yet, agates are found mainly in volcanic rock that presented an original temperature of 2,000°F. Who knows what pressures are also involved in such a hot environment? We find other agates in sedimentary rocks that have never been above ambient temperatures.

Adding to the confusion is the host of local names given to agates by collectors. Some of the major groups of agates include; banded fortification agates, moss agates and dendritic agates.

No wonder there is still confusion and disagreement over how agates form! For this, the focus is on fortification banded agates.

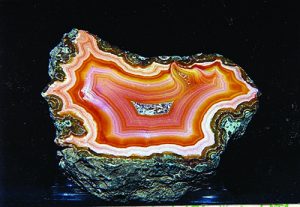

What are Fortification Banded Agates?

It would not be an overreach to consider banded fortification agates as the dominant and most popular form of agates from the beginning right up to today. After all, they are the most eagerly sought and bring some of the highest prices. Banded agates are formed in volcanic environments and are the agates that usually come to mind when agates are considered.

Outside In?

One group of agate theories says agates form from outside forces once in place.

In this theory, the cavity in which an agate develops can start empty or contain undifferentiated silica gel. Later, the necessary ingredients for agates arrive. In other words, the original agate material arrived after the hot lava flows were in place. A typical theory of this type proposed by Peter Keller in his doctorate thesis is based on his observations of the beautiful banded agates of Mexico’s Sonora and Chihuahua Deserts.

Dr. Keller theorized that Mexican agates started as open gas cavities in volcanic rock, which were later invaded by mineral-rich waters from nearby hot springs. These waters carried the necessary silica as well as metal ions for color. Keller related the banding to fluctuating wet-dry seasons common in the desert. As the hot springs surged forth, the waters would slowly infuse into the open cavities in the lava, forming a sequence of colored bands.

Inside Out?

The other group of theories suggests everything was present in the lava’s cavity – silica gel and impurities. The agate then formed internally from all the present material.

A theory proposed along these lines was offered by Charles Schaub, a noted collector from the East Coast. Simply stated, Schaub proposed that the hot molten lava was moving along small globs of silica when gel would slowly gather together to form a larger sphere of silica gel, which was then locked in place as the lava cooled. This process meant the silica gel formed its own “cavity.” The banding then formed as the temperatures in the gelatinous mass slowly dropped and band after band developed with each temperature change. The colors are because of included mineral salts like iron oxide, which crystallized as temperatures varied during cooling.

Today’s Agate Formation Theories

Each of these theories simply does not explain everything, a current problem, even with today’s leading theories.

The current theory is from theorist M. Landmesser. He suggests that agates form in large cavities in a rock that is already filled with what he calls a pore solution. The natural material is a hydrothermal silica solution from which quartz separates, moving from an area of high concentration to an area of lower concentration. Over time a colloid forms and adheres to the walls of the cavity. Colloid particles of different sizes develop separately in bands.

Entrance or Escape Channel

One of the odd features in some banded agates is called either an entrance or an escape channel. Many banded agates have distorted banding that curves away from the normal linear pattern and extends to the agate’s outer rind. This development is cited as proof that material entered the cavity to form the agate, later hardening, and leaving behind the banded entrance path in a funnel-like design. The problem with this is that many of these funnel-like patterns don’t contact the outer rind of the agate. There is often a gap between the rind and the upper end of the distortion.

A Logical Theory

More logical is the theory that such distortions are because of internal heat and pressure within the agate nodule itself. Once formed, an agate is a closed system and any temperature or pressure increases are trapped inside. Such heat and accompanying pressure do happen because the silicon dioxide bands are made of millions of micro-crystals of quartz, estimated to be about 30,000 to an inch. When silicon dioxide leaves a solution and crystallizes, heat is released. Imagine the heat generated by those millions of quartz crystals as they form quartz bands. With an increase in heat, there has to be an increase in pressure in a closed system. The bands themselves are still in a plastic-like state and can react to that pressure. The pressure can distort the still flexible bands if it pushes the bands toward the path of least resistance. In some instances, it may reach the rind, but often does not and instead results in the odd funnel form.

Development of Agate Band Colors

Another common question among agate collectors has to do with how the various colors get into the agate bands. The colors are because of oxidized ions of metallic elements like iron and manganese. You might think the micro-crystallized quartz that forms bands tightly fit together. They do not. This fact is proven when dye is introduced into an agate with metallic solutions. They can get into the bands because quartz crystals do not grow as smooth-sided crystals. They do not. They twist as they develop, and crowded together, there are microscopic spaces between them into which the sub-microscopic metal ions of iron oxide and others can enter. The process involves bringing color to an otherwise drab gray agate band. Keep in mind such ions can vary in both size and only enter spaces where they can fit.

BOB JONES

Other Minerals Present

Another feature seen in some agates is the crystals of some other minerals like aragonite or zeolite that grew attached to the agate cavity’s inner walls. They seem to have formed before the agate bands formed.

These initial crystals don’t survive. They rarely are coated with silica. Much more likely, they are replaced by the quartz during agate formation. In effect, these crystals are quartz pseudomorph after what first formed, usually aragonite or zeolite.

In some agates, a small form that is not attached to anything seems to be floating in the agate. These are probably molecules of the coloring agent like iron oxide. Every compound in solution has an affinity toward molecules of itself. It’s an electrical attractive and is why crystals grow in solution. It also adds to an agates beauty and mystery, a mystery yet to be solved.

This story about agate formations previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Bob Jones.