By Steve Voynick

As early as 600 BCE, Greek naturalists were intrigued by a mineral that mysteriously attracted iron and other pieces of the same material. They named it magnes lithos, or “stone of Magnesia” (the origin of the word “magnet”), after the site in Anatolia (now western Turkey) where it was discovered.

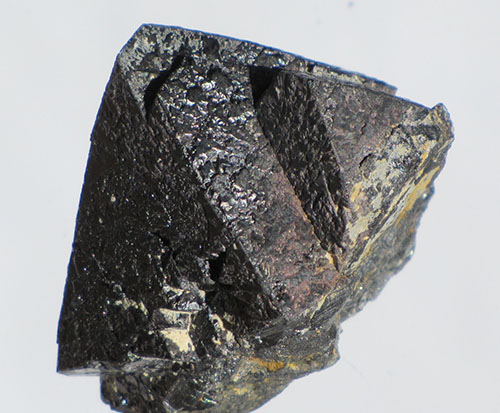

That mineral was the lodestone variety of magnetite, or iron oxide. Magnetite crystallizes in the isometric system as octahedrons or dodecahedrons. It has an iron-black color with occasional blue iridescence, a Mohs hardness of 5.5-6.5, and a specific gravity of 4.9-5.2. Its most interesting physical property is its natural magnetism.

Natural Magnetism

Magnetism, one of the fundamental forces of nature, is produced by the movement of electrons. Metals are considered magnetic when the poles of their individual atoms, or ions, align to create the dipole effect of polarization. An example of polarization is the north and south poles of bar magnets, in which like poles repel and opposite poles attract.

Magnetite’s simplified chemical formula is Fe3O4. However, its actual chemical composition is more complex, because the iron is present as both ferrous (Fe+2) and ferric (Fe+3) ions. Magnetite is therefore correctly described as a ferroferric oxide with an empirical formula of Fe+2Fe+32O4.

Within magnetite crystals, oxygen ions form a closely packed, cubic lattice in which the iron ions are positioned at the interstices (openings) and occupy distinct tetrahedral and octahedral sites. This arrangement permits a continuous flow of electrons between the ferric and ferrous ions that is always aligned in the same directional plane.

This electrical vector generates a magnetic field, just as a wire conducting an electrical current generates a magnetic field. The directional electrical vector and its magnetic field keep magnetite’s molecules precisely aligned to maintain the mineral’s magnetism.

Examining Magnetic Susceptibility

Because of its atomic structure, iron has the greatest tendency of any metal to become magnetized. Several other metals, including cobalt, nickel, and a few rare earth elements can also become magnetized, but to a much lesser extent.

The term “magnetic susceptibility” refers to a mineral’s ability to become magnetized. Two factors determine the level of magnetic susceptibility. First is the amount of iron, nickel or cobalt present; second is the degree of atomic alignment permitted by the mineral’s structure. On the magnetic-susceptibility scale, a completely nonmagnetic mineral is ranked at zero.

Magnetite, the only mineral that exhibits strong or obvious magnetism, has a magnetic-susceptibility rating of 20.

While trace magnetism exists in many minerals, only about 20 exhibit significant magnetic susceptibility. All contain iron, either as their sole cation or part of a compound cation. The second most magnetic mineral is chromite (iron chromium oxide), which has a magnetic susceptibility only one-twentieth that of magnetite.

Critical in Early Seafaring Navigation

When magnetite was originally emplaced as an accessory component of molten magma, the earth’s magnetic field aligned its iron ions to make magnetite mildly magnetic. But atmospheric lightning sometimes increases this magnetism. As an instantaneous, massive discharge of electrons, lightning generates a very brief, but extraordinarily intense, local magnetic field. When lightning strikes close to a surface deposit of magnetite, its intense magnetic field forces the magnetite molecules into a more perfect alignment to substantially increase the magnetism of that particular mass of magnetite.

Such highly magnetized pieces of magnetite are called “lodestone”. By the 1400s, mariners worldwide were using lodestone to magnetize the iron needles in navigational compasses. The word lodestone entered the English language around 1500 and literally means “guiding stone”, alluding to its use in compasses.

Magnetite and its lodestone variety were the only known sources of magnetism until 1819, when Danish physicist Hans Christian Øersted learned that magnetic fields also existed around wires that conducted electrical currents. Only after the electromagnet was invented in 1824 did scientists begin to understand the cause of the magnetism in magnetite. However, full explanation awaited the emergence of particle physics in the early 1900s.