Story by Steve Voynick

That quartz and turquoise are most often associated with the Native American experience in collecting, mining, utilizing and trading minerals is not surprising. Both minerals played prominent roles in Native American culture in the many centuries prior to European contact. Huge amounts of microcrystalline quartz were fashioned into essential tools and weapons. And turquoise, which was widely mined and traded in the Southwest, remains the iconic Native American gemstone today.

Trading Minerals

But the overall Native American experience with minerals and mineral resources goes far beyond far quartz and turquoise to include obsidian, muscovite, halite, fluorite, soapstone, galena, pipestone, hematite, clay, sandstone and copper. While Native Americans simply collected some materials from the surface, they obtained others from underground mines that they developed without the benefit of iron implements. Minerals were sometimes valuable commodities that were traded across North America in commerce systems that are just now beginning to be understood.

The legacy of the Native American experience with minerals survives today in hundreds of geographic-place and geologic-formation names such as Obsidian Cliff, Flint Ridge, Cliff House Sandstone, Pipestone National Monument, and Copper Culture State Park. Many Native American mining sites can still be seen today in national and state parks and monuments and at historical, archaeological and geological points of interest. Other sites are actually being mined today, recreationally or commercially or traditionally, with centuries-old methods.

Most important to Native American cultures were the flint and chert varieties of microcrystalline quartz. Consisting of tightly interlocked microcrystals and lacking a visible crystalline structure, these quart varieties are abundant, hard (Mohs 6.5-7.0), and durable. Their conchoidal fracture enables them to be flaked into sharp-edged tools and weapons such as arrowheads, spearheads, knives and scrapers. Flaked microcrystalline quartz comprises the bulk of all Native American artifacts.

Awareness of Commodities

Native Americans were utilizing flint and chert well before 12000 BCE and are the first mineral commodities in what is now the United States to be systematically mined and traded. Important sources include deposits at present-day Flint Ridge State Memorial, in south-central Ohio, and Flint Hills National Monument, in the Texas Panhandle. Both have outstanding museums that focus on Native American uses of flint.

Native Americans were also mining the jasper deposits at today’s Flint Run Archeological District, in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, before 8300 BCE.

Chert mining at the “Spanish Diggings”, a 400-square-mile area of Platte and Converse counties in eastern Wyoming, began 10,000 years ago and continued until the time of European contact. At the Spanish Diggings, Native American miners excavated through as much as 30 feet of solid quartzite to reach veins and nodules of chert.

The Flint Hills of eastern Kansas and adjacent Oklahoma, a region named for its many outcrops of flint, was another important source of microcrystalline quartz.

Projectile Points Reveal Context

Native Americans also occasionally collected macrocrystalline quartz, notably in Arkansas’

Ouachita Mountains, an area familiar to mineral collectors today as a classic locality for colorless, transparent rock crystal. Archaeologists have contextually dated the oldest known artifact fashioned from Arkansas rock crystal—an arrowhead—to 9000 BCE.

While exploring this region in 1541, Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto noticed that many Native American projectile points were fashioned from rock crystal. In 1819, geologist Henry Rowe Schoolcraft visited sites where rock crystal still covered the ground. Native Americans told Schoolcraft how their ancestors had collected rock crystal for ceremonial and ornamental purposes. Archaeologists have recovered Arkansas rock crystal artifacts at cultural sites as distant as Florida and Illinois.

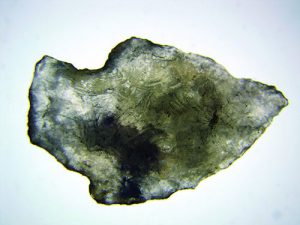

Native Americans considered obsidian the best flaking material of all. Obsidian is a mineraloid, a noncrystalline, minerallike material of indefinite composition. As a natural volcanic glass, it forms from the rapid solidification of rhyolitic (silica-rich) magma. Consisting of silica and lesser amounts of feldspar and ferromagnesian minerals, obsidian is softer than quartz; its typically gray to black colors are due to traces of iron and magnesium. With its conchoidal fracture and amorphous structure, flaked obsidian edges are much sharper than those of microcrystalline quartz.

Eyeing Obsidian in Yellowstone National Park

Unexposed obsidian contains only traces of water but, when flaked, its newly exposed surfaces begin to hydrate very slowly, albeit at a constant rate. Using a geochemical technique called obsidian-hydration dating, geochemists can correlate the extent of hydration to the approximate age of flaked obsidian artifacts. Obsidian artifacts can also be “sourced” by matching their unique chemical compositions with those of obsidian from known deposits—information that enables archaeologists to reconstruct ancient trade systems.

The most culturally significant Native American obsidian source was Yellowstone National Park’s Obsidian Cliff, a rhyolite ridge that was first quarried 12,000 years ago. Obsidian from Obsidian Ridge has been found at cultural sites as distant as Ohio and eastern Canada.

And large quantities of obsidian from Native American quarries at central Oregon’s Glass Buttes and northern California’s Glass Mountain were traded along the Pacific Coast from Mexico to Canada.

Versatile Soapstone

Native Americans made great use of soapstone, also called steatite, as a mineral carving material. Soapstone is a metamorphic rock consisting mainly of talc (hydrous magnesium silicate) and lesser amounts of chlorite, carbonate, amphibole and pyroxene minerals. The softest of all minerals at Mohs 1.0, soapstone has a “soapy” feel; its colors range from off-white to shades of gray, blue, brown and green.

Talc content determines soapstone’s hardness. The softest and most desirable carving grades contain about 80% talc and are easily cut. Native Americans carved soapstone into such decorative and utilitarian objects as bowls, cups, cooking slabs, boiling stones, beads and figurines. Deposits in the heavily metamorphosed Appalachian Mountains provided a steady source of soapstone for many Native American cultures in the Eastern part of what is now the United States.

California’s Tongya culture began mining soapstone around 5000 BCE on Santa Catalina Island, carving and trading soapstone bowls that later became known as ollas (Spanish for “pots”). The Tongya fashioned these bowls from in situ soapstone, leaving the exposures riddled with hundreds of bowl-sized, circular depressions that can still be seen today.

Exploring Pipestone

By 7500 BCE, the Inuit of Alaska were carving soapstone into amulets, ceremonial objects, and children’s toys. The Inuits’ use of soapstone peaked after European contact, when white traders created a market for large quantities of carvings. Today, Inuit soapstone carvings are Alaska’s most popular souvenir.

Another carving medium was pipestone, or “catlinite”. Pipestone is argillite (not a mineral name), a 1.7 billion-year-old, metamorphosed mudstone. Consisting of tiny particles of the hydrous aluminosilicate minerals muscovite, kaolinite and pyrophyllite and the hydrous aluminum oxide mineral diaspore, pipestone is exceedingly fine-grained.

Its rich, reddish-brown color is due to tiny particles of hematite. With a hardness of Mohs 2.5, pipestone was easily worked with quartz tools. It occurs only in southwestern Minnesota as thin layers between strata of hard quartzite.

Naming Conventions

Plains cultures have prized pipestone for 2,000 years as a material for ceremonial pipes.

The Lakota Sioux consider it a sacred stone that represents moral, religious and ethical duty, and symbolizes brotherhood and peace. The Pawnee and Sioux were master pipestone carvers and fashioned the T-shaped calumet pipes that whites called “peace pipes” because of their use at treaty ceremonies. Cultural sites as distant as the Gulf Coast have yielded pipestone artifacts.

The alternate name “catlinite” honors the painter George Catlin, who visited the Minnesota pipestone quarries in 1835. Catlin depicted pipestone quarrying in his classic oil-on-canvas painting “Pipestone Quarry on the Coteau des Prairies”, which now hangs in the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum. He also recorded the Native American legend that the Great Spirit decreed that pipestone be used only for ceremonial pipes. Poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow mentioned the Minnesota pipestone quarries in his epic poem “The Song of Hiawatha”.

Today, Pipestone National Monument at Pipestone, Minnesota, preserves 53 ancient pipestone pits, each about 15 feet long and 15 feet deep. This national monument allows Native Americans to mine pipestone on a permit basis using only traditional methods. Mining is difficult, for much durable quartzite must be removed to reach the pipestone layers at, or slightly below, the water table. An Ojibwa tribal group, the Keepers of the Sacred Tradition of Pipemakers (www.pipekeepers.org), maintains the ancient legacy and skills of pipestone mining and carving.

Moldable Material

Many Native Americans, especially those in the Mississippi Valley and the Southwest, made ceramic pottery, storage vessels, funerary urns, beads, figurines, and ceremonial objects by shaping and firing clay into hard, durable objects. The earliest examples of North American pottery originated in the Southeast about 5,000 years ago.

“Clay” is a general term for fine-grained earth consisting of tiny particles of hydrous aluminosilicates of sodium, potassium, calcium and magnesium. These clay particles, each only about 0.002 mm in size, have sheet structures and perfect cleavage. They occur in surface sediments from the weathering of feldspar-group minerals. The most abundant clay minerals are kaolinite and montmorillonite.

When wet, clays have a plastic consistency and are easily moldable. Native Americans purified clay by drying, grinding and screening it. Then they added finely ground, nonplastic tempering materials such as ash, crushed bone, silt, limestone, shell, or muscovite to prevent shrinkage and cracking during firing. They molded the clay manually, often by coiling ropelike lengths into desired shapes. After firing, the wet clay dried, lost its plasticity, and hardened into permanent, molded shapes.

Tempering Techniques

Tempering imparts distinctive qualities to ceramics that are often source-unique. In the Southwest, Taos potters tempered clay with finely ground muscovite that also imparted an attractive glitter to their ceramics. The Hopis, on the other hand, used pure kaolinite clay that did not require tempering.

Several Mississippian and Eastern North American cultures mined and traded muscovite (hydrous potassium aluminum oxysilicate), a mica-group mineral that crystallizes in the monoclinic system as thin, tough, elastic, sheetlike crystals. It has a Mohs hardness of 2.0-2.5 and a vitreous to pearly luster, and it occurs in aggregates of well-developed crystals called “books”. With its perfect, one-directional cleavage, muscovite cleaves easily into thin, semitransparent, silvery-white sheets.

The Hopewell culture, which occupied the Ohio River valley 2,000 years ago, traded flint from south-central Ohio’s Flint Ridge for sheets of muscovite from the pegmatites of western North Carolina. Hopewell craftsmen fashioned these thin sheets into translucent effigies of human hands and torsos, hawk talons, and reptiles. The Hopewell culture also obtained obsidian from Wyoming’s Obsidian Ridge and copper from Upper Michigan’s Lake Superior region.

Mining in Michigan

Upper Michigan, the world’s richest source of native copper, was the site of one of the most impressive examples of Native American mining. The first Native Americans to arrive in the region 10,000 years ago found pieces of native copper lying on the ground. Copper mining reached its peak after 4000 BCE, with Native American miners making thousands of excavations, some as deep as 20 feet. They hammered and annealed this native copper to make tools, weapons and ornaments that are among the earliest known examples of metalworking.

Little is known about these ancient Native American copper miners. Archaeologists refer to them as the Old Copper culture and conservatively estimate that they mined at least 500,000 pounds of native copper. Artifacts made from this copper have been found at cultural sites in Canada and throughout the Ohio and Mississippi valleys. Regional museums, including one at Copper Culture State Park in Oconto, Wisconsin, which preserves an Old Copper culture burial site, display thousands of copper artifacts.

Native Americans in the East and the Southwest also mined native copper, albeit on a much smaller scale. In 1804, near present-day Silver City, New Mexico, Apaches led Spanish prospectors to a source of native copper that has since been developed into the huge Chino open-pit copper mine, which is still producing today.

Salt Mining in the Sierra

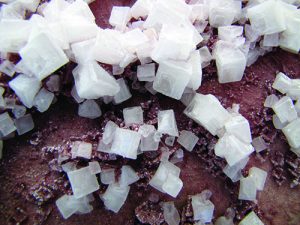

Archaeologists have also documented evidence of Native American salt mining. In eastern

California’s Sierra Nevada, the Miwok “salt basins” include 360 depressions carved into solid bedrock. Each about 4 feet wide and 2 feet deep, these depressions served as evaporation pans for saline water from nearby springs. Their number and size indicate that the Miwok engaged in a sizeable salt trade.

The Sinagua culture mined rock salt 2,000 years ago near what is now Camp Verde, Arizona. This deposit contained halite (sodium chloride) and lesser amounts of such evaporite salts as glauberite (sodium calcium sulfate), thernardite (sodium sulfate), mirabilite (hydrous sodium sulfate), and gypsum (hydrous calcium sulfate). Native American salt miners created a network of 70-foot-deep underground workings that were discovered by modern salt miners in the 1920s.

About 1,200 years ago, Native Americans in the Southwest began mining turquoise, a hydrous calcium aluminum phosphate. Turquoise was a sacred stone that became a valuable, widely traded commodity. Turquoise mined in the Southwest has been found at cultural sites in the Southeastern United States, Canada, the Caribbean, and southern Mexico. To define these ancient turquoise-trading systems, archaeologists use secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) analysis to link the hydrogen-copper isotope ratios of turquoise artifacts with their unique Southwestern sources.

Prolific Cerrillos Hills

The most prolific of these turquoise sources is the Cerrillos Hills near present-day Santa Fe, New Mexico, where Native Americans developed mines with hundreds of feet of underground workings. By 900, Cerrillos was regularly supplying turquoise to the nearby Chaco Canyon culture, where craftsmen fashioned and traded huge quantities of turquoise beads and pendants. Prosperity from the turquoise trade supported Chaco’s rapid cultural development between 1150 and 1280.

The Southwest also has many examples of the Native American architectural use of another mineral commodity: sandstone. Chaco Canyon, now part of Chaco Canyon National Historical Park, is a showcase of Pueblo stone architecture. Pueblo architecture reached its peak about 1,000 years ago at Chaco Canyon with construction of complex, modular, multistory structures like the Pueblo Bonito ruin, with 650 rooms and 60 underground ceremonial kivas. Laid out in accordance with astronomical observations and aligned to maximize solar heating, the striking geometric symmetries of Pueblo Bonito indicate an obvious understanding of architectural design.

Many Southwestern Pueblo structures are built of aptly named Cliff House sandstone. This 77 million-year-old, fine-grained, marine sandstone separates along laminations into flat pieces several inches thick that trim readily into “bricks”. Native American masons set these pieces into walls and secured them with an adobe-type mud. With their excellent design and durability, many examples of Pueblo stone architecture have survived for over a millennium.

Other examples of this architecture are the ruins at Arizona’s Wupatki and Canyon de Chelly national monuments and at Colorado’s Mesa Verde National Park.

Use of Mineral Pigments in Pictographs

Mineral pigments were also important Native Americans, who used them in pottery and pictographs and for personal adornment. Shades of red were derived from powdered hematite (iron oxide); yellow from ochre (a mixture of hydrated iron oxides); black from pyrolusite (manganese dioxide); and white from powdered kaolinite, gypsum or caliche (a calcite encrustation). Blue and green pigments were rare and have been found only where Native Americans had access to outcrops of the copper-carbonate minerals malachite and azurite.

Cubic crystals of galena (lead sulfide) were occasionally collected and traded for ornamental and ceremonial purposes. The Hopewell culture obtained galena from what is now the Southeastern Missouri Lead district; its craftsmen also collected colorful fluorite crystals from the present-day Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar district to carve into figurines. Examples of Hopewell uses of minerals are displayed at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, near Chillicothe, Ohio.

So while ancient Native American cultures will always be most readily associated with flint and turquoise, they also mined, utilized and traded a much broader array of rocks and minerals.