Story and Photos by Steve Voynick

Native Americans once “owned” all the turquoise deposits in what is now the United States, not in terms of today’s legal definition of ownership, but by virtue of discovering the deposits and having been first to mine, work, and trade the turquoise. But after Europeans arrived, the turquoise mines became and remain, for the most part, Anglo property.

The exception is the North Star Mine in Cripple Creek, Colorado. The North Star is owned by Clint Cross, a registered member of the Sokoki Tribe of the Abenaki Nation of Missisquoi, along with his wife Louisa McKay and Australian partners Graham and Anna Slater. Clint is the only Native American to currently own and operate an active turquoise mine.

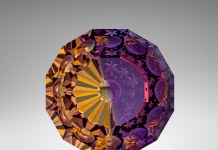

North Star Mine turquoise is distinguished both by the mine’s Native American ownership and its superb, natural gem qualities of saturated blue-green colors, distinctive matrix patterns, and extraordinary hardness.

Expanding on a Turquoise Tradition

of North Star turquoise

incorporates stable pieces of

the diorite host rock.

Although new on the market, North Star turquoise already has a heritage as the latest chapter in the story of Cripple Creek turquoise. Cripple Creek, of course, is first and foremost synonymous with gold. Perched 9,500 feet high on the western slope of Colorado’s iconic Pikes Peak, the town is named for a nearby rocky creek notorious for crippling cattle. Cripple Creek was born in an 1892 gold strike; just eight years later it had grown into a booming city of 20,000 residents with 400 mines turning out one million troy ounces of gold per year.

The first miners at what is now Cripple Creek, however, were not gold miners, but Native Americans who collected turquoise from exposed veins. Their points and scrapers of flaked chalcedony are found today along with bits of turquoise on the surface of the North Star Mine.

“Turquoise was not mined in Vermont where I was born and raised,” Clint admits. “But my people—the Abenaki—recognized its spiritual significance and passed that along to me. So owning a turquoise mine today means a great deal to me—it’s something I feel I was meant to do.”

Turquoise has long held a special place in the beliefs of Native Americans, especially those cultures indigenous to the turquoise-rich Southwest. While Native Americans admired turquoise for its beauty, they also venerated it for its spiritual, religious, and ritualistic significance.

Cultural Connections

Some cultures considered turquoise a part of the sky that had fallen to Earth; its blue-green colors symbolized the connection of Earth with sky, and body with spirit. In Navajo and Hopi creation legends, turquoise represents sky, water, bountiful harvests, health, and protection.

It is also an element in Zuni rituals and Navajo rain ceremonies. Apaches linked turquoise to rain at the end of rainbow and attached bits of the stone to their bows in the belief that it guided their arrows.

Cultures far beyond the Southwest also recognized turquoise’s sanctity. Turquoise mined in the Southwest has been recovered from indigenous cultural sites as distant as Florida, Canada, Central America, and the Caribbean.

The Southwest has more than 200 significant turquoise sources, most related to shallow, oxidized copper deposits in New Mexico, Arizona, and Nevada. Top-quality turquoise, however, is rare. Fewer than a dozen sources consistently yielded turquoise in which color, durability, and hardness did not require artificial enhancement. Most of these sources have been mined out and others lost to open-pit copper mining.

Turquoise Deposits in Colorado

As a relatively minor source of turquoise, Colorado has just five

significant deposits, all in the south-central part of the state. Among them are Turquoise Chief Mine in Lake County, the Last Chance Mine at Creede in Mineral County, the King Turquoise Mine in Manassa, Conejos County, Villa Grove in Saguache County, and Cripple Creek in Teller County. The North Star Mine at Cripple Creek is now Colorado’s only active turquoise source.

Colorado turquoise occurs in a variety of mineralogical environments. At the Turquoise Chief, it is present as veinlets in granite; at the Last Chance, it is found in heavily oxidized sections of the silver-rich Amethyst Vein. Villa Grove turquoise occurs as veinlets in altered gabbro. At Manassa, Native Americans originally mined turquoise from underground workings in solid basalt, and the site was later mined commercially. At Cripple Creek, turquoise veins are found in altered diorite.

Turquoise (CuAl6)(PO4)4(OH)8·4H2O) is hydrous copper aluminum phosphate, a secondary mineral that forms under specific hydrological and mineralogical conditions from the weathering of rocks rich in aluminum, copper, and phosphate minerals.

The Cripple Creek deposit is located within the Central Colorado volcanic field, an extensive area of volcanism that dates the early Oligocene Epoch some 34 million years ago. All local mineralization is related to the Cripple Creek caldera, a collapsed volcanic system created when eruptions alleviated magmatic pressure, causing a volcanic dome to subside and fracture.

Exploring Ores

Mineral-rich, hydrothermal solutions associated with repetitive surges of magma then emplaced metallic gold and the gold-telluride minerals calaverite and sylvanite. The Cripple Creek caldera is a circular mass of brecciated rock five miles in diameter. Gold and gold-telluride minerals occur within its core in rich veins and pockets. Surrounding this core is a much larger area of disseminated, low-grade gold mineralization. The high-grade core fueled Cripple Creek’s mining boom of the 1890s; today, a modern, open-pit mining operation exploits the low-grade ores.

Copper mineralization occurs only in a small area at the caldera’s northwestern edge, where it was emplaced by hydrothermal solutions that circulated though a fault in the diorite host rock. This north-south-oriented fault controlled the emplacement of all Cripple Creek turquoise. Interestingly, bits of native gold are occasionally seen within the turquoise itself.

When gold was discovered at Cripple Creek in 1892, an abundance of turquoise lay scattered about the surface. But most miners were concerned only with gold; only a few collected turquoise, usually as a novelty item to trade for drinks in the local saloons.

Musician and part-time gold prospector Wallace C. Burtis was first to take a serious interest in Cripple Creek turquoise. In 1939, he bought a claim, not for its poor showing of gold, but for the turquoise that lay on the surface. Burtis renamed the claim the Florence Lode, taught himself gem cutting, silversmithing, and jewelry making, and began mining, working, and selling turquoise. He passed these interests and skills on to his son Wallace F. (Wally) Burtis who continued mining and later sold stones under the name “Burtis Blue Turquoise.”

Celebrating Heritage Through Mining

By 2010, Wally and his wife Joanne, getting on in years and needing help with mining and marketing, hired Clint Cross and Louisa McKay. Both already experienced with Cripple Creek turquoise, Clint and Louisa took over mining operations at the Florence Mine and marketed Burtis Blue Turquoise at gem-and-mineral shows.

Clint took an indirect route to Colorado from his Abenaki birthplace in northern Vermont. The Abenaki—the name means “People of the Dawn”—are an Algonquin-speaking culture that once populated present-day Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, and adjacent sections of Canada.

Today, 6,000 Abenakis, mostly in Vermont, maintain tribal unity to preserve their language, customs, and traditions. Lacking federal recognition as a tribe, however, they have no reservation. But because Vermont recognizes the Abenaki, they qualify for educational funds and use of the designation “native made” on their arts and crafts.

As a boy, Clint took pride in his heritage and learned the traditional Abenaki skills of hunting, fishing, trapping, and wilderness survival. He later ran a construction outfit in Florida, then a trail-riding business in Louisiana. Moving to Colorado in 1998, he did some prospecting, which led him into turquoise mining in Cripple Creek. He and Louisa, who is also interested in mineral collecting and the outdoors, married in 2008.

Building a Future Through Turquoise Mining

In 2017, when Wally and Joanne Burtis became uncertain about the future of their Florence Mine, Clint and Louisa began considering their own future in turquoise mining.

“We were always interested in the property north of the Florence Mine,” Clint says. “The geology indicated that the turquoise veins extended onto that property. Although it had never been mined, Louisa and I had found turquoise right on the surface. When we learned that the property was available, we saw a chance to own a turquoise mine.”

Clint and Louisa acquired the property in August 2017, named it the North Star Mine, and began mechanical exploration into the soft, weathered diorite. They soon exposed a heavily altered seam—a section of the fault that had controlled local turquoise emplacement. Further excavation revealed erratic veins and pockets of turquoise within the crumbly, hematite-stained, yellowish-brown diorite.

Thanks to his previous construction experience, Clint performs the mechanical excavation himself, which halts at the first sign of turquoise veins. These appear in the host rock as unremarkable, dark trends that would escape the attention of an inexperienced eye. But closer inspection and a bit of rock-pick work quickly reveals the bright, blue-green colors of North Star turquoise. While the veins themselves are thick enough to provide gem turquoise, they sometimes “blossom” into pockets that can yield solid turquoise an inch or two thick and several pounds in weight.

Shades of Pure Turquoise

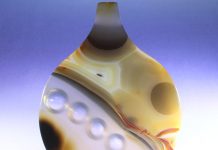

Almost all turquoise mined in the world today is not of gem quality. It

this inch-long, flaked

chalcedony arrowhead

and turquoise on the

undisturbed surface of

the North Star Mine.

lacks the color intensity to appeal to gem and jewelry buyers, the structural integrity to withstand cutting stresses, and the hardness necessary to polish nicely and endure jewelry wear. Turquoise is abundant on today’s jewelry market today because most of it is inferior material that has been treated to improve color, structure, or hardness.

Pure turquoise has a bright, clean, “robin’s-egg”-blue color. But varying quantities of iron and other metals that substitute for copper within its crystal lattice often shift this basic blue color toward green.

The colors of North Star turquoise range from blue and greenish-blue to bluish-green and green, and occasionally even to a delicate purple. This broad color variation indicates multiple-phase emplacement in which each depositional phase varied in chemistry.

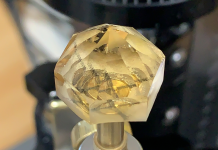

Turquoise hardness generally ranges from Mohs 5.0 to 6.0, depending upon degree of silicification and, to a lesser extent, the nature of accessory-metal substitution.

Silicification occurs when silica-rich solutions deposit microcrystalline quartz within the turquoise pores to fix and intensify color, seal pores, and substantially increase hardness.

Testing Turquoise

Well-silicified turquoise resists both abrasion and discoloration from the absorption of skin oils. North Star Turquoise, which is unusually well-silicified and contains traces of corundum (aluminum oxide, Mohs hardness 9.0), actually attains a Mohs hardness of 6.5 or higher.

North Star turquoise is completely natural and has the documentation to back it up. Stone Group Laboratories, a leading gem-testing laboratory, has subjected it to X-ray-fluorescence, raman, fourier-transform-infrared, and ultraviolet-visible-near-infra-red-spectroscopy analyses. By revealing chemical composition, molecular structure, and bonding characteristics, these tests can detect the presence of plant dyes, epoxy stabilizers, and potassium compounds that are the “fingerprints” of turquoise treatment.

All North Star turquoise is accompanied by a Stone Group Laboratories statement attesting to the fact that it is untreated. Clint and Louisa also maintain direct control over all aspects, from mining to marketing.

Matrix is another distinctive feature of North Star turquoise. Matrix—the visible, non-turquoise mineralogical materials within the turquoise—enhances the overall appearance of turquoise gems by accenting and adding interesting patterns to the basic blue-green colors. Much North Star turquoise has a particularly attractive matrix of golden-brown veins and thin, black hairlines. The golden-browns are limonite, a variable mixture of iron hydroxides and oxides; the black hairlines are pyrolusite, or manganese oxide.

Turquoise Tumblers

This sharply defined, intensely colored matrix results from unusually high heat levels that accompanied the hydrothermal-deposition process. One especially attractive matrix type consists of oxidized-iron compounds that reflect light in the manner of bright, burnished copper.

pieces of both blue and green

North Star turquoise.

After mining, North Star turquoise is tumbled to remove adhering bits of the yellowish-brown host rock. Clint’s “tumblers” are two rotary cement mixers, each of which he loads with water and 150 pounds of rough turquoise. The turquoise is first tumbled for two 12-hour periods and screened after each run, then put through a final three-day tumble. The tumbling medium is turquoise bits that are too small for inlay or jewelry use.

Clint and Louisa then sort the tumbled turquoise by size and shape. Turquoise to be retained in its natural shape is sandblasted with 80-grit garnet at a pressure of 165 pounds per square inch to smooth the surface and remove any undesirable features. Stones destined for cutting are shaped on a 10-wheel lapidary unit with increments from an 80-grit rough-shaping wheel to a 14,000-grit fine-polishing wheel.

Clint and Louisa, together with Katy Pickens, a silversmith from nearby Breckenridge, Colorado, make their own jewelry.

“Personally, I don’t copy existing jewelry styles or traditions,” Clint says. “My Abenaki name is ‘Stand Alone,’ which describes my preferences in turquoise jewelry. Rather than adhering to existing styles and traditions, I consider each stone to be unique in color, size, shape, matrix, and spirit. The spirit of each stone tells me how it should be used in jewelry.”

Fault Line Exploration

Preliminary exploration along the fault line and its associated turquoise-vein systems indicate that turquoise reserves at the North Star Mine are sufficient for decades of mining. Looking toward the future, Clint has already assured that the North Star Mine will always remain in Native American hands. Should something happen to Clint, and neither Louisa nor son Clevalden wish to continue mining, the property will go to the Abenaki Nation in perpetuity.

When I last visited Clint and Louisa at the North Star Mine in November of 2018, they had mechanically exposed a new fault section in the morning, then collected 15 pounds of rough turquoise in the afternoon. Before wrapping up the day’s work, they made another find—a one-inch piece of turquoise lying alongside a flaked chalcedony arrowhead.

“That point reminded me that my ancestors once gathered turquoise from this same deposit,” Clint said with a smile, “and I think they’d be pleased that I’m here today.”

Clint and Louisa are regular vendors at national gem-and-mineral shows in Tucson, Houston, and Denver, and also at Colorado regional shows in Colorado Springs, Creede, Buena Vista, Woodland Park, and Fairplay.

For further information visit www.northstarturquoise.com or contact Clint Cross and Louisa McKay at (802)782-7330 or crossfamily1000@aol.com.

Author: Steve Voynick

A sci-ence writer, mineral collector, and former hard rock miner, he is also the author of many references including, “Colorado Rock Hounding” and “New Mexico Rockhound-ing.”

A sci-ence writer, mineral collector, and former hard rock miner, he is also the author of many references including, “Colorado Rock Hounding” and “New Mexico Rockhound-ing.”