By Bruce McKay

Kingman turquoise has been a favorite of mine for many decades, and I have often used it in my goldwork. I believe the rich blue of Kingman should be accented with the rich yellow of gold. The first gemstone mine sales office I ever visited was to buy Kingman turquoise back in the late 1970s, and I still have some of the rough material from that purchase. With that, I was very pleased when Marty Colbaugh invited me to tour the Kingman mine itself.

I met Marty and his son Josh, first thing in the morning just outside of Kingman, Arizona at Colbaugh Processing, headquarters of the mine, and we hopped into their truck to head to the mine. It is a short drive from the main office to the mine, and during the drive, the two men talked about Kingman Mine history and their family’s involvement.

Kingman Character

Kingman Mine is in the Mineral Park area of the Cerbat Mountains in northwestern Arizona. This mountain range is primarily Precambrian gneiss, and many gold, silver and copper mines have operated there in recent history. The Kingman Mine is inside a copper mine. It is within two areas inside the copper mine, in Ithaca Peak and Turquoise Mountain. Currently, mining takes place on the face of Turquoise Mountain, as Ithaca Peak has been removed. There are many decades of reserves still to be mined, and the turquoise occurs in areas of sulfides and sulfide oxides. The upper sulfide oxide areas produce turquoise with more greens, and as you go deeper into the sulfide areas, the quality of the turquoise gets better and a richer blue.

Turquoise is present in veins, and as the veins go deeper into the ground, the quality of the material improves. Veins as thick as 40 feet have been found in this mine.

When Marty’s father, S.A.” Chuck” Colbaugh, first began mining Kingman, the diggings of Native Americans were still visible. At one time, he exposed a tunnel that had goatskin water bags and stone hammers still inside. The American Indians had been using turquoise from this mine for 1800 years or more, most often for personal adornment and trade purposes. Kingman turquoise traded through the ancient trade routes has been found as far as Mexico City. Archaeologists have been able to date the Mexico City area turquoise to 200 AD and have traced it back to this mine.

Chuck Colbaugh cut his first lapidary stone in 1929. He worked in the mining industry as a heavy equipment operator, welder and foreman in Battle Mountain, Nevada. Then he moved to Globe, Arizona, to work in the area mines. It’s believed the elder Colbaugh became the first person to stabilize Kingman turquoise after he put some chalky turquoise into epoxy. This discovery wouldn’t be his last. Colbaugh was an inventor and tinkerer and at one time held the patents on all the automatic cabochon cutting equipment in the US.

In 1962, Chuck Colbaugh heard that the Mineral Park Copper Mine was going to open, so he got permission to remove turquoise from the mine. Two years later, the Duval Mining Company began copper mining and Colbaugh retained his contract rights to mine turquoise within the mine. To this day, the Colbaugh family still has those contract rights, now with the Origin Mining Company of Canada. The copper mine is not currently in production but could restart any time Origin feels the market conditions were right.

Exploring Brilliant Blue Veins

Continuing with the tour, we drove up to the mine gate, and Marty punched in the security code to enter. After going through the gate, we switched to driving on the left side of the road. The drivers of the huge mining dump trucks have poor visibility to the sides, so for safety, all vehicles drive on the left side so the truck drivers can see other vehicles. While no large dump trucks are currently working in the mine since it is dormant, but the safety rules remain and are followed. After a short distance, we arrived at the large pit below the very tall mine face, but I was disappointed to see no actual excavation taking place. We were told someone had just headed to town for parts to repair vehicles, so they halted until they could get things running again.

Rather quickly, I could see blue veins of turquoise hundreds of feet up the face of the mine, but well below the top of the face. In order to mine the vein the crews cut benches, starting at the top of the face and work down. Each bench is 50 feet high and 25 feet wide, and the excavated rock is pushed off the bench and into the bottom of the mine pit until it is 150 feet deep. At this time, the rock is removed, ground, and graded into three sizes of rock. It then goes through the sorting shed.

There are two sorting sheds, and within each, two people were hard at work, pulling turquoise off conveyor belts. If they have hit a particularly rich area of material, the rock is recirculated through the belts to make sure nothing is missed. The sheds are small and air-conditioned.

The group is very strict on safety and have never lost an hour over an accident. They routinely get top ratings for safety from the Mining Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) and recently received a “0” citation report after an inspection. A no citation report is so unusual that MSHA sent another inspector out to confirm, and he also turned in a “0” citation report.

All-In-One Operation

As we returned to the mine headquarter, I toured the manufacturing facility. The

company does all of the manufacturing of the products they sell. They used to have all of their stone cutting done in China, but eight years ago, they decided they could do it cheaper themselves and have had great success in doing so. Today the company employs nearly 50 people, with crews working in the mine, the manufacturing facility, and in the office and salesroom.

Carrying on the stabilization tradition set forth by Chuck Colbaugh, a great majority (95 percent) of the rough material removed from the mine is stabilized or pressed into bricks. This material is too soft or too small to be formed into cabochons or beads, but nothing goes to waste, and Colbaugh Processing is among the leaders in the stabilization of turquoise, using a stabilization process with optically clear resin under no pressure. The stones weigh the same after stabilization as before. In a recent development, Rolex is manufacturing a Kingman turquoise dial watch, and the company only wanted stabilized material for the consistency and lack of color change.

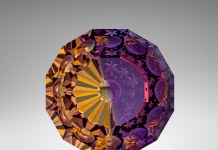

A small percentage of their mined material is unusable even for stabilizing. New technology has created colorful pressed bricks ready to be cut into gems with a bronze spider webbing. Marty Colbaugh bought this process and perfected it into a product that cuts into beautiful, consistent stones. The pressed bricks come in many colors, some dyed, and others with turquoise mixed with other stones such as malachite, azurite, Spiny Oyster shell and pink opal. The company’s Mojave Green bricks got their name when a Mojave Green rattlesnake wandered into the shop. However, I don’t think the actual snake is in any of the bricks.

A unique combination of brick is the blue and orange version created by mixing turquoise with orange-colored Spiny oyster shells. These shells are a byproduct of Mexico’s shell food industry, which means no oysters had to die for the production of the jewelry. Josh Colbaugh suggested the brick combination to his father since Native American silversmiths used the Spiny Oyster shells in combination with turquoise. Marty felt otherwise but was wise enough to let Josh experiment with this notion, and now it is their best seller. I think this combination looks great, and I bought some bead strands.

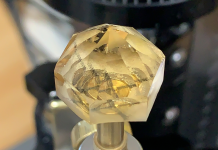

Whether the stones are natural, treated or made into bricks, they go into the cutting shop to become cabochons, beads, cell phone case accessories, and candle holders, among other items. With this process, the company uses mass-production techniques to preform, then hand cut and polish. They make cabs using a preform cabochon cutter from Germany, not the one that Chuck Colbaugh invented. It turns out the efficiency of the German machine is more important than nostalgia in this modern workshop.

Intrigued By Equipment and Creativity

I was fascinated by the bead cutting equipment as I had never seen how beads were made. But, my favorite machine was the dopper. It uses hot glue heated with natural gas to dop up to 26 cabs at once. They are perfectly centered and are ready to go into the automatic preform machine. After preforming is done, workers at banks of cabbing machines put an excellent polish on a wide variety of calibrated shapes and sizes, and then the stones are ready to go to the salesroom.

The salesroom is new and an improvement from the previous space. It is big, provides a lot of room to wander around and look at the bead strands, rough material, trays full of calibrated cabs, cases full of finished jewelry, and the bricks manufactured in the shop. My favorite part of the sales area is the rough material room just off the main floor. This room contains bins full of treated and natural rough material in various sizes and qualities. I picked out some slabs that are natural veins 4” x 4” and 1/3” thick, plenty big enough to cut a nice belt buckle cab.

The Kingman that I drool over most is the spiderweb, and there is plenty to choose from in both stabilized and natural. There is spiderwebbing in various colors such as blue and black or white, but I am fond of black spiderwebbing. I have cut stones from it and have found the webbing to be consistent as I cut through stone. I was pleased to find some blue webbing just like the first pieces of Kingman I bought 40 years ago. It has dark blue webbing with a light blue interior, very beautiful.

Colbaugh Processing is a family operation with the third and fourth generations of the Colbaugh family involved with the company. Hopefully, the fourth generation will keep this family business moving forward, and with the known reserves of the mine, they will continue to have turquoise to mine and cut and sell.

The mine office is just seven miles north of Kingman, Arizona. If you find yourself in the area and are a lover of turquoise, you need to stop in. There is enough for everyone to drool over, trust me. For more information, visit www.colbaugh.net.