By Bob Jones

One of the more attractive and popular lead minerals is vanadinite, a lead chloro-vanadate.

Vanadinite as a collector mineral has been around for years but seldom rose to high status as a display mineral until quantities of brilliant large red crystals surfaced in Morocco. The Moroccan specimens far exceed in size, beauty, and collector appeal anything found elsewhere. Prior to the Moroccan discoveries, vanadinite tended to be just average half-inch sized crystals with uncommon examples of larger sizes. Color ranged from good red to brownish yellow and were found in many desert localities.

Foundation for Formation

Vanadinite is formed as a secondary mineral in desert lead deposits often associated with mimetite and pyromorphite. When first found, vanadinite was recognized as a lead mineral with reference to its red or brown color, which explains why the type locality mineral for vanadium was called “plombo rojo” in Mexico.

The discovery of the new element vanadium developed into a complex story in which vanadium ended up being discovered twice in two different minerals in two different countries by two different scientists 30 years apart!

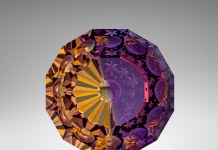

Vanadinite most often forms as simple hexagonal prisms of modest size as very attractive bright red to orange-red color crystals. Moroccan vanadinite makes up for its lack of crystal size by completely covering a matrix in tightly packed clusters and stacks of brilliant rich red multi-crystal heaps.

The initial investigation of vanadinite, which was suspected of containing a new element, was by Andres Manuel del Rio Fernandez of the Royal College of Mines, Mexico City. He was organizing the College’s mineral collection and came across a brown lead mineral labeled “plumo rojo del Zimapan.”

Investigating Vanadinite

The initial investigation of vanadinite, which was suspected of containing a new element, was by Andres Manuel del Rio Fernandez of the Royal College of Mines, Mexico City. He was organizing the College’s mineral collection and came across a brown lead mineral labeled “plumo rojo del Zimapan.”

He decided to investigate the specimen. The crystals were from the Purisma del Cardonel mine, near Zimapan, Mexico. In 1801, after much study, he found a new substance that he named panchromium after the many colors it had exhibited during his chemical studies. He later changed the name because of its fine blood-like red color, calling it erythronium.

To have his work verified, del Rio sent his results to Europe by ship. Much to his dismay, the ship carrying his work on plumo rojo del Zimapan (erythronium) crashed and sank, deep-sixing his work.

As if that were not enough to discourage him, noted German scientist, Alexander von Humbolt, whom he respected, had checked his work and concluded that del Rio had only found a known metal element, chromium. Del Rio accepted Von Humbolt’s findings and did a paper about his work, but without announcing a new element, titling the paper “Discovery of Chromium in Brown Lead from Zimapan.”

Keep in mind that the time from the 1600s onward were known as the halcyon years of chemical and scientific research, during which time new elements were being discovered regularly as chemistry emerged from the Dark Ages of alchemy.

Process of Discovery

Once scientists realized undiscovered elements were still hidden in minerals, the race was on to study minerals and seek out their contents. Discoveries came fast and often, adding more and more to the list of known elements. Yet, by the 1850s there were still only 58 native natural elements known when Mendeleev developed his Periodic Table of Elements. (For more information, see my “On the Rocks” column >>>)

It was 30 years after del Rio’s mistaken assumption of finding something new when a doctor turned mineral researcher, Nils Gabriel Sefstrom, working on iron ore in Taberg, Sweden, determined the exact contents of this complex ore. One substance from the ore seemed softer than expected, so Sefstrom investigated it but only extracted a tiny amount of something new, too small to check further.

Sefstrom continued his search and finally concluded that cast iron had more of his unknown substance in it. He guessed correctly that the slag waste from this smelter might be worth investigating. Sefstrom was able to isolate the hidden metal element, which turned out to be del Rio’s erythrnium. Sefstrom named the new element vanadium after Vanadis, Norse goddess of love and beauty. Did you also know Vanadis is also known as Freyja/Freya?

Certainly the element vanadium is well named, for when it is found in minerals, they are almost always colorful and of exceeding beauty. There is a good reason why vanadium causes minerals to be colorful. It is a transition metal element. That means its atomic structure is such that its last orbital of electrons around the nucleus can contain anywhere from two to five electrons called valence electrons.

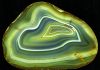

They have the unique ability to absorb certain wavelengths of color in the visible light spectrum, causing a color in the mineral. In vanadinite, when light enters the crystal’s surface, these electrons cause the red color to be present. Sometimes vanadinite can be yellow or brown for the same reason, depending on the number of electrons in that last orbital. When vanadium occurs in other minerals and gems like emerald, the color we see is green thanks to chromium or, less often, vanadium. Diopside can be green and axinite can have a blue color, thanks to vanadium.

Arizona’s Vanadinite Offerings

Arizona has been a wonderful source of vanadinite. I’ve been very successful in

collecting vanadium for decades. The main sources of my success in Arizona are the Apache mine, the Old Yuma mine, and the Greyhorse mine. To a lesser extent Mammoth-Saint Anthony, J.C. Holmes, Red Cloud, and Ford mines have been good producers of vanadinite. Yet, I would be the first to acknowledge the world’s finest vanadinite specimens are from Morocco.

Quantities of superb red vanadinite came on the market after the 1960s and thrilled everyone. The bright red hexagonal crystals raised the level of vanadinite specimens to a much higher collector level. Dealers were eager to obtain specimens, and it wasn’t long before they began to head for Morocco. A home movie was even made by dealer Victor Yount, a longtime friend, when he went to Morocco and, after a difficult travail, brought back superb specimens in quantity.

At the time Yount went to Morocco, he was living in Spain where his father had been sent to negotiate military bases with Dictator Franco. Vic’s life in Spain is what movies are made of. Through his mother, he even worked as an extra on well-known movies including “Patton.”

Be that as it may, to make the journey to Morocco, not exactly a safe haven, and Vic bought a bullet proof car from the wife of the Portuguese Ambassador. He shipped the car to Morocco and headed for Milbladen in the Upper Mouloya Lead Mining District. Unfortunately, his car suffered some flat tires in the middle of nowhere. Stuck, he was rescued when a Bedouin tribe arrived. He didn’t know what would happen, so he pulled out his guitar and started entertaining his rescuers while one of them went to civilization and got tires.

Mining for Vanadinite

Once in Milbladen, Vic was able to obtain a large selection of fine vanadinite specimens. Back on the coast, while returning with his vanadinite, he found out it was illegal to ship minerals out of Morocco. At this point, Vic got creative. He went to a marketplace and bought a bunch of cooking pots and large carpets. The vanadinite specimens were packed into the pots or rolled up in the carpets for shipping. Mission accomplished.

The miners who worked the lead mines in Morocco were also adventuresome. In one mine, they were working in a raised stope with a really good vanadinite vein. Some uncommon rain in the area caused the water table to rise, blocking the access tunnel to the vanadinite vein. Instead of quitting, the miners decided to swim underwater to the raised stope and continued to mine vanadinite.

Two other regions in Morocco that have produced superb vanadinite are Touissit, Ouijda-Angad province, where bright red crystals in black manganese oxide occur, and Taouz, where the vanadinite is found on goethite. The quality of the vanadinite from these lead sources rivaled Milbladen. No wonder Morocco is credited with the world’s finest vanadinite.

For most of us, the vanadinite we collect is not the quality of Morocco, but we sure enjoy collecting it. I spent many a day underground at the Apache mine near Globe, Arizona, and always came away with nice specimens.

Vanadinite Paradise

The Apache mine was operated during World War II for vanadnium used to harden steel. The red crystals were so common and so loosely attached to the breccia rock matrix that miners could actually scrap the crystals off the walls and rocks and ship car loads of loose vanadinite crystals to the smelter.

For collectors, the Apache mine was vanadinite paradise. If you had an open day, you could climb down into the Apache and crawl through partially collapsed tunnels to get to exposed veins filled with loose chunks of breccia rock covered with red crystals. Sometimes you would break into an open seam and sit for an hour or two plucking out pieces of vanadinite without using tools to extract the red beauties. We hardly ever used a hammer, only using a blade to loosen the rock pieces that were often attached lightly to each other and covered with vanadinite. The crystals were never large, under a half-inch, but so completely covered the gray rock as to be very attractive.

After a successful trip to the Apache, I’d often take a flat or two of these red beauties to the next meeting of the Mineralogical Society of Arizona club. There I would set the flat out so older members who could not go underground could have something nice. Those were the good old days of collecting.

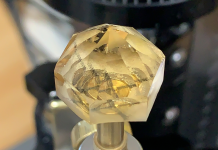

Arizona has also produced some fine pyramidal vanadinite. Most vanadinite is simple hexagonal crystals with flat terminations. But the J.C. Holmes prospect near Patagonia just north of the Mexican border is the source of lustrous yellow pyramidal vanadinite crystals. The larger crystals reach just about an inch. Most crystals form in tight adamantine clusters that are very showy. This prospect was very limited in scope, with one or two exposed veins on the surface. The host rock is really hard and tight, so specimens are not common. If you have an opportunity to obtain a J.C. Holmes pyramidal vanadinite, you’ve got a winner.

While vanadinite is described in the literature as an uncommon mineral, Morocco has made it more common, and the Arizona localities have added their measure of red beauty as well. They have certainly given me many, many hours of pleasure collecting them underground. Your collection deserves one of these bright red lead chloro-vandate specimens with the complicated history.

Author: Bob Jones

Holds the Carnegie Mineralogical Award, is a member of the Rockhound Hall of Fame, and has been writing for Rock & Gem since its inception.

Holds the Carnegie Mineralogical Award, is a member of the Rockhound Hall of Fame, and has been writing for Rock & Gem since its inception.

He lectures about minerals, and has written several books and video scripts.