Editor’s Note: This is one of 10 Mexican locales recognized for mineral production. View the rest of the list see >>>

The Naica mine lies about 100 km south of Chihuahua and Santa Eulalia. Like Santa Eulalia and Ojuela, it is a Carbonate Replacement Deposit, but Naica has a much different mining history because the vast bulk of her ore tonnage is sulfides that were not discovered until 1955. Perhaps a million tons of oxide ores were mined from the mid-1800s to the 1930s, but these workings were largely sealed off when sulfide mining began in 1956, so oxide minerals are quite rare from Naica. Naica’s orebodies are a series of 88 separate vertical chimneys of sulfide and skarn ore 20 to 80 m in diameter that extend vertically for up to 700 m. The tops of these bodies tend to be very vuggy, with cavities commonly lined with ore sulfides, calcite, sky-blue anhydrite and colorless, green, blue and purple fluorites.

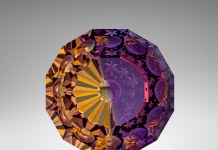

Fluorites are remarkably abundant as crystals from 2 to 20 cm and show a wide range of crystal habits and forms-often in a single crystal. Sharp “spinel-law” twins are rare but can be exceptionally well developed.

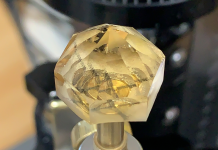

However, Naica is undoubtedly best known for its lack of color in the form of abundant colorless gypsum crystals. The waters that circulate through the mine, and have done so for eons, are hot (50°C) and saturated with calcium sulfate derived from bedded anhydrite at depth. On cooling slightly they precipitate gypsum everywhere from the insides of pumps, pipes, and sumps to caverns in the surrounding limestone.

Gypsum grown in the mining infrastructure tends to be sharp, elongate and limpid, with local green or golden color imparted by iron. Miners facilitate this by throwing things into the sumps, so crystals grown on wire, old boards and miscellaneous bits of mining junk are common. But gypsum was deposited for eons before human intervention, and numerous large caverns lined with crystals have been found in the mining process.

The “Cave of the Swords” and the “Xochitl Caverns” were famous for many years as a

source for the 1-2 m gypsum crystals that grace the Harvard Museum and the cavern restoration in the Denver Museum of Natural History (Gressman, 1988). These were completely outclassed in 2000 when miners deepening some workings blasted into the “Cave of the Giants.”

This incredible cave contains dozens of giant transparent gypsum crystals a meter or more across and up to 11 meters long; early images of miners seated on the crystals were dismissed as being Photoshopped! The cave has now seen more than 15 years of intense scientific study (Otalora and Garcia-Ruiz, 2014), and several films have been made, featuring scientists in orange space suits that keep them cool in the 55°C heat of the cave.

The size of these crystals is perfect protection because, between their weight and their length, they are impossible to remove from the mine.